How Public Street Lighting Appeared in Bucharest and Who Paid for “the Light on the Street”

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

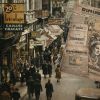

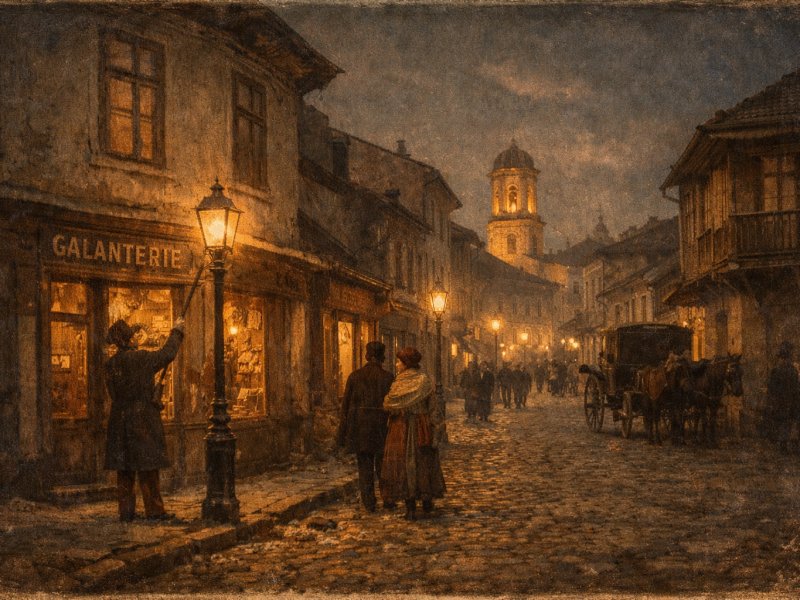

A nighttime stroll through today’s Bucharest, with all its charming chaos and neon lights promising shawarma or sports betting on every block corner, gives us a sense of safety we take for granted, without a second thought about what things were like two hundred years ago. You flip a switch, the street lights up, most of the time, and your only real concern is dodging electric scooters strategically abandoned in the middle of the sidewalk.

And yet, the history of lighting in the capital is a full-blown comedy of errors, a fascinating mix of accidental innovation, Ottoman-style bureaucracy, and Western ambition unfolding in a city that, for a long time, preferred to go to sleep with the chickens. If we could teleport to Bucharest in the year 1800, we would discover that the only sources of light were the moon, the stars, and, occasionally, the spark from a sword striking cobblestones during a neighborhood brawl.

The darkness of old Bucharest had a material density, an almost solid consistency that swallowed you whole. Leaving the house after sunset was an act of extreme courage, an adventure reserved for the reckless or for those equipped with a solid bodyguard and a sturdy torch. Without lighting, the city turned into a maze of mud and danger, and “Little Paris” looked far more like a vast, damp cave.

The road toward civilization and the electric bulb was long, paved with the smell of rancid tallow and petroleum, but the story deserves to be told, especially because it shows how inventive we become once we grow tired of smashing our toes in the dark.

Groping in the dark, torch-bearers, and the terror of nighttime mud

At the beginning of the 19th century, Bucharest operated under a simple rule: the night belonged to thieves, guards, and evil spirits. Anyone who absolutely had to cross the city after dark turned to the services of the masalagii.

These were colorful characters, often burly servants, who carried a masala, a primitive kind of torch made from rags soaked in pitch or resin, fixed into a metal holder. The masala smoked terribly and dripped flammable material everywhere, but it did provide a protective circle of yellowish light.

Boyars and wealthy merchants traveled accompanied by these fire carriers, creating small, mobile islands of light in an ocean of darkness. For the common man, however, night meant total isolation. Streets without paving and riddled with trap-like holes became impassable. The risk of stepping into a deep pit or being relieved of your wallet was a mathematical certainty.

The first timid attempts to light public spaces came more from policing concerns than aesthetic ones. The authorities realized criminals preferred darkness and decided to ruin their working conditions. Admittedly, the initial solution was rudimentary: tavern keepers and inn owners were required to keep a light burning at their entrance. The effectiveness of this measure was questionable, since a single lantern with a tallow candle, battered by wind and rain, barely managed to light its own pole, let alone the street.

The era of Prince Caragea and the rise of bored lamplighters

The turning point, or at least the attempt to organize the chaos, came during the reign of Ioan Gheorghe Caragea. Although his name is historically associated with a devastating plague, Caragea also had administratively revolutionary ideas for his time. In 1814, he ordered lanterns to be installed in the main areas of the city, marking the official birth of public street lighting.

The system relied on vegetable oil and tallow. The lanterns, tin boxes with glass panes that were often smoke-stained, were hung from poles or house walls. This is where a legendary figure of urban folklore enters the scene: the fanaragiu, later known as the lamplighter. He was the official responsible for lighting, extinguishing, and maintaining the lanterns.

In theory, the lamplighter was supposed to clean the glass, top up the oil, and make sure the flame burned brightly until dawn. In practice, lamplighters formed a caste of bored, poorly paid workers who performed their duties with exemplary indifference.

Chroniclers of the time wryly noted that the lanterns illuminated “mostly to everyone’s disadvantage.” The oil was often of dubious quality, and the wicks charred quickly. Worse still, lamplighters had a habit of skimming some of the oil for personal use or resale, leaving the lanterns to flicker weakly. Even so, the mere presence of these points of light changed the city’s psychology. People began venturing out after dusk, social life found its courage, and Bucharest started to resemble a European city, albeit one that smelled strongly of burnt grease.

Who picked up the bill? The tax on darkness and the burden on property owners

Financing this timid pyrotechnic spectacle proved to be a thorny issue from the very start. City officials then, much like today, showed a marked aversion to spending public funds on frivolities such as “seeing at night.” Initially, the costs fell squarely on property owners.

The system worked on the basis of civic obligation: anyone owning a house on a street was required to provide lighting in front of their property. This meant purchasing the lantern, the fuel, and paying whoever maintained it. Unsurprisingly, enthusiasm among property owners was nonexistent. Many conveniently “forgot” to light their lanterns or used tiny candles that burned out after an hour.

Seeing that private initiative was grinding along poorly, the Agia, the police of the time, took control by imposing a special tax. Thus appeared the “light levy” or “lantern tax.” Money collected from townspeople was used to pay an army of lamplighters and to purchase fuel centrally. Even so, corruption and inefficiency caused funds to evaporate mysteriously, leaving streets frequently plunged back into darkness. Citizens paid their dues, only to retain the privilege of tripping over the same holes, now faintly visible just before impact.

The oil revolution and the world moment of glory in 1857

Here the story becomes genuinely interesting and allows for a bit of local pride. While major European capitals like Paris and London still relied heavily on gas lighting, which required an expensive network of pipes, Bucharest made a surprising technological leap thanks to local natural resources and the ingenuity of two brothers, Teodor and Marin Mehedințeanu.

In 1857, Bucharest became the first city in the world to be publicly lit with kerosene. This claim, occasionally contested by Viennese sources, remains a point of local pride supported by documents. The Mehedințeanu brothers managed to distill crude oil into a clear liquid with little odor, burning with a steady, bright flame that far surpassed rapeseed oil or tallow.

The contract signed with the city’s Eforia, the public administration and precursor of City Hall, called for replacing old lanterns with new ones adapted for kerosene. The change was dramatic. The light was white, strong, and, most importantly, cheap. Romanian kerosene cost far less than imported vegetable oils or the coal required to produce gas.

Suddenly, Bucharest became a glowing city. Foreign travelers remarked with surprise on the quality of lighting along Podul Mogoșoaiei, today’s Calea Victoriei, comparing it favorably with Parisian boulevards. This was the moment when “Little Paris” began to make sense, at least visually.

The British, the French, and the maze of gas pipes

The kerosene monopoly lasted for a while, but progress demanded sacrifices and, above all, lucrative international contracts. Toward the end of the 19th century, pressure mounted to introduce gas lighting. Gas offered the theoretical advantage of centralized ignition and even greater light intensity.

In 1871, the mayor at the time, Scarlat Kretzulescu, granted the public lighting concession to an English company led by a certain Mr. H.G. Slade. The British arrived, dug trenches, an activity that became a permanent feature of city life, laid pipes, and installed elegant cast-iron lanterns. Gas lighting brought with it a new urban aesthetic. Lanterns turned into pieces of street furniture, and their greenish-yellow glow created a romantic atmosphere, perfect for discreet romantic encounters or political conspiracies on street corners.

But relations with foreign concessionaires were always tense. Contracts were bulky, clauses often favored the companies, and gas prices fluctuated. On top of that, the British had the irritating habit of cutting off gas supply whenever City Hall delayed payments, plunging the city into total darkness as a form of commercial protest.

Citizens, already paying hefty taxes for lighting, found themselves collateral damage in the war between bureaucrats and capitalists. It was a transitional period in which kerosene lamps coexisted with gas lights, each with its own supporters.

The electric miracle and the twilight of the romantic era

The end of the 19th century delivered the final blow to flame-based lanterns. Electricity, the mysterious and invisible force, was knocking at the city gates. Early experiments were timid and exclusive. The Royal Palace on Calea Victoriei was the first building to benefit from electric lighting, quickly followed by the National Theatre and Cișmigiu Garden.

For the average Bucharest resident, seeing an electric bulb was a cultural shock. A light that did not smoke, smell, or flicker and turned on instantly felt like pure wizardry. In 1882, a first demonstration installation operated at Cotroceni Palace. Then, gradually, the “electric plant” began stretching its wires across the city.

The transition was, unsurprisingly, expensive. City Hall had to invest colossal sums, and the “lighting tax” became a permanent feature of urban life. Who paid for the light? The citizen, of course, either directly through a bill for those lucky enough to have home connections, or indirectly through local taxes covering street lighting costs.

The introduction of electricity marked the end of an era. The lamplighter, ladder on his back and oil can in hand, vanished into history, surviving only as the subject of anecdotes. Streets became safer, commerce pushed deeper into the night, and the pace of life accelerated. The city may have lost some of the gothic mystery of dancing shadows, but it gained, for its citizens, the simple right to walk the streets without breaking their necks.

Stay lit, little bulb

Today, public lighting in Bucharest is a complex system managed by computers, sensors, and intervention teams carrying tablets instead of torches. We pay for it through taxes and local levies, a modern continuation of the old “light duty.” Even if we still complain when a neighborhood goes dark due to a malfunction, the reality is that we live in a luxury our great-grandfather, with his sooty oil lamp, would have considered pure magic.

The history of Bucharest’s lighting is also a valuable lesson about progress and the fact that it always comes with a cost, with a transition period that smells a bit worse, and with a dose of Balkan-style improvisation. From tallow to LEDs, the journey has been lit by the ambition to turn night into day and by the eternal desire of Bucharest residents to clearly see where they step, to avoid the potholes of history or, more precisely, those of local administration.

You may like: Famous Boulevard Names: Pavel Kiseleff, the Russian General Who Loved Romania and Gave Us the First Constitution