What the interwar society press of Bucharest looked like

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

Interwar Bucharest woke up every morning with the newspaper over coffee and an unstoppable desire to find out who had compromised themselves the night before. The society journalists of the era mastered a refined, almost surgical art of revealing scandalous stories without mentioning any names, of destroying reputations while maintaining the appearance of elegance, of saying absolutely everything with a simple initial followed by three dots.

Interwar Bucharest was an era when everyone read between the lines, and between the lines lay the whole story.

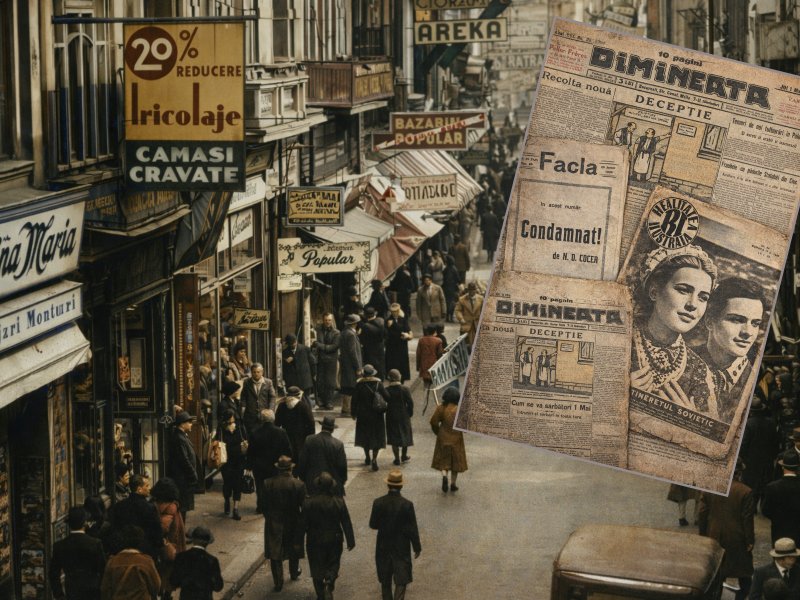

Newspapers that made and broke reputations

Realitatea Ilustrată, the queen of elegant gossip

Launched in 1926 by the Adevărul trust, Realitatea Ilustrată quickly became the bible of Bucharest high society. The publication combined spectacular photographs with texts full of innuendo. A lady photographed at the Hippodrome next to a gentleman who, alas, happened to have the same initial as the lover whispered about in the salons, was already a scandal with documents and witnesses. The "innocent" photograph spoke for itself.

N.D. Cocea's Facla, society's alarm whistle

Nicolae D. Cocea, a staunch socialist and feared pamphleteer, turned Facla into a whip for the aristocracy and the upper middle class. Cocea had an unmistakable technique: he described in detail the crew, the servants' livery, the color of the car, and the model of the hat. Who could have owned "an emerald green Rolls-Royce, driven by a chauffeur in a burgundy livery, stopping daily in front of a hotel on Calea Victoriei where a blonde artist from the National Theatre lives"? The whole capital knew.

Dimineața or the art of initials

Dimineața, a widely circulated newspaper, had perfected the system of initials. The classic formula looked something like this: "Mrs. X..., wife of distinguished diplomat Y..., was seen discreetly leaving the summer residence of Colonel Z..." The Bucharest reader, trained in the art of decoding, solved the puzzle before finishing his coffee.

Rampa – for lovers of theater and actresses

Rampa magazine, dedicated to the world of theater, also covered the private lives of artists with a mixture of admiration and malice. Actresses received reviews for their roles, but also for their "roles" in their private lives. A big industrialist caught at the premiere in the box of a diva became the subject of commentary for weeks.

The secret dictionary of the gossip press

Journalists of the time had developed a veritable coded language. Here are a few examples of translations from "gossip" into Romanian:

"A lady of high society" = aristocrat or wife of a politician/banker; identity could be deduced from further details

"A young heir known for his passion for cars" = a rich kid, probably a spendthrift with mistresses

"Artistic friendship" = a long-term adulterous relationship, tacitly accepted by society

"Prolonged indisposition" = suspected pregnancy, admission to a sanatorium, or elopement with a lover

"Recreational trip to Vienna" = clandestine abortion (Vienna being the preferred destination for such procedures)

"Amicable separation" = scandalous divorce, hushed up with big money

"A well-known figure in the business world" = elegant swindler or stock market speculator.

Capșa was society's boxing ring

The Capșa café on Calea Victoriei functioned as a veritable gossip exchange. Society journalists had reserved tables, and information circulated faster than the waiter with his tray. It is said that much of the "news" in the press originated here, at Ion Minulescu's table or in the corner frequented by journalists.

An appearance at Capșa or a prolonged absence became a subject of speculation. If an aristocratic couple suddenly stopped having lunch together, journalists were already writing paragraphs full of "rumor has it that...".

The sublime technique of the "octopus" or how to avoid lawsuits

Socialite journalists lived under the constant threat of libel lawsuits. Lawyers were expensive, and convictions could mean the closure of the publication. That is why the avoidance techniques had become simply ingenious.

This "octopus" technique involved dispersing information across several articles or editions. On Monday, there was a mention of "an elegant car seen in Băneasa," on Tuesday there was an article about "hat fashion in diplomatic circles," and on Wednesday there was a photo from a society event where, purely by chance, the car, the hat, and the lady in question appeared. Each article was innocent in itself, but their combination said it all.

The "provincial" technique began with the phrase "A reader from the provinces writes to us that he noticed in Bucharest..." The newspaper merely conveyed information it had received, and the blame lay with the anonymous reader. A kind of... "legend has it."

The "rhetorical question" technique remains the favorite of pamphleteers: "What brings the well-known banker M... so often to the Armenian quarter, far from his marital villa in Cotroceni?"

Major scandals and their treatment in the press

Through an initial to eternity

Zizi Lambrino, Carol's first wife (marriage annulled), appeared in the press as "Mrs. L..." or "the former acquaintance of a foreign prince." The custody battles over their son, Mircea, provided ample material for the international press, which was eagerly picked up and commented on "with regret" by Romanian journalists.

Princess Bibescu and her salons

Marthe (Martha) Bibescu, writer and aristocrat, frequently appeared in the society pages, treated with a mixture of fascination and envy. Her salons at Mogoșoaia and her relationships with European intellectuals generated endless commentary. The press noted the princess's "distinguished guests," leaving readers to speculate on the exact nature of these visits.

The case of "Duduia" and the elephant in the room

The biggest taboo subject, but paradoxically the most discussed "indirectly," concerned the Royal House. King Carol II and Elena Lupescu provided endless material for the press, but the law of lèse-majesté imposed maximum caution.

Opposition or scandal newspapers, such as Facla or Curentul (at certain times), used creative paraphrases. Elena Lupescu became "that lady," "the person in the shadows," or, most often, references were made to her hair color. A news item about "the fashion for redheads dominating politics" provoked bursts of laughter in cafes, because the allusion directly referred to Elena's enormous influence over the King.

Sometimes, journalists would place two seemingly unrelated news items side by side. One column would feature official praise for the King, and right next to it, an anecdote about an ancient king manipulated by a courtesan. The reader would instantly make the connection.

Constantin Mille's Adevărul could publish an article about "female influences in European politics" without mentioning Romania, leaving readers to draw their own conclusions. After Carol's abdication in 1925 and his exile in Paris with Elena Lupescu, the press wrote about "the Romanian living on the Riviera with a compatriot," a technically correct but devastatingly clear formulation.

Pamfil Șeicaru and the palace built in silence

Pamfil Șeicaru, the uncrowned king of the interwar press and editor of the newspaper Curentul, elevated blackmail to the status of a respectable institution. It was said in town, with admiration mixed with fear, that Șeicaru had two types of articles in his drawer: those that were published and those that remained there for a fee.

There is a persistent urban legend that the imposing Curentul newspaper building (which still stands today, opposite the Military Club) was built largely with money received for not publishing certain devastating investigations into the industrialists of the time. Șeicaru wrote scathingly, attacked violently, and then, suddenly, the subject disappeared from the pages of the newspaper. Silence fell, and the newspaper's accounts grew. This "attack and pause" strategy had become an extremely profitable business model.

Blackmail newspapers and "negative subscriptions"

In addition to the respectable press, interwar Bucharest also had a less honorable fauna: blackmail newspapers. These obscure publications sent "subscription offers" to wealthy families, with a very clear implicit message: pay up and your name will remain off our pages.

The capital's police recorded dozens of complaints annually, but concrete evidence was difficult to obtain. The threats were elegantly worded, the subscriptions seemed legitimate, and the line between journalism and extortion remained conveniently blurred.

Curiosities from the society press of the interwar period

Photo manipulation was already an art form. Skilled technicians could "remove" a person from a group photo or, conversely, "add" someone to a compromising company.

The Continental Restaurant at the Athénée Palace had a discreet entrance on a side street, used by couples who preferred discretion. Gossip columnists posted informants at both entrances.

The Baneasa Racetrack was the ideal place for "accidental" encounters. A lady could claim that she met a gentleman by chance at the races. Newspaper photographs showed that the "accident" was repeated with suspicious regularity.

Sinaia and Peleș Palace generated entire pages of society reports during the season. Who received an audience, who was seen walking on forest trails, who was suspiciously absent from receptions—everything was noted and published.

The advent of the telephone complicated the lives of journalists. Meetings could be arranged without witnesses. But servants remained a gold mine of information: a small financial incentive and the information flowed freely.

The "Parisian" style of Bucharest journalism

The Romanian society press eagerly imitated the French model. French expressions abounded in the text, lending an air of refinement to even the most vulgar gossip. "Un five o'clock" replaced the afternoon snack, "un rendez-vous" sounded much more intriguing than a simple meeting, and "un ménage à trois" elegantly described situations that would otherwise have offended readers' ears.

The ideal society journalist was a man of the world, frequenting the same places as his subjects, knowing their habits, friendships, and enmities. This proximity gave him access to information, but it also exposed him: articles "with hidden meanings" could be written about him as well.

The interwar society press in Bucharest remains a fascinating document of a society that valued appearances above all else. The art of saying without saying, of accusing without naming, of destroying without leaving traces was a true way of life.

Readers of the time were trained in decoding, connoisseurs of characters and intrigues, participants in a collective game of high-class gossip. Initials and ellipses turned newspapers into romanesques. And everyone had the key.

Today, when tabloids publish everything explicitly, with compromising photos and shocking statements, the refinement of the interwar period seems almost nostalgic, harking back to an era when even scandal had good manners.

You may also like: Famous boulevard names: Octavian Goga, founder of the magazine Luceafărul, Prime Minister of Romania