The passions of the nearsighted teenager of Bucharest: Mircea Eliade rowed on the Danube, climbed mountains, and played oina in the neighborhood

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

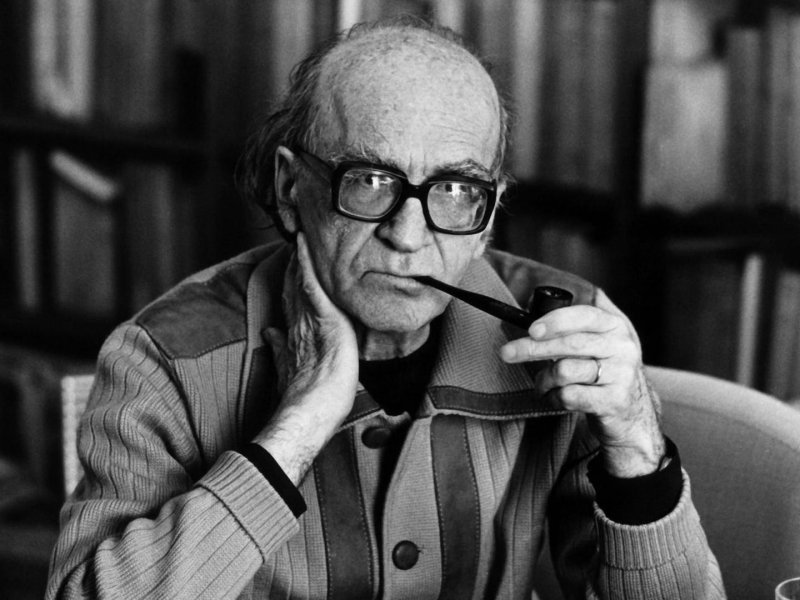

Before becoming one of the world’s most important historians of religions, Mircea Eliade was a curious, energetic, and restless child, fascinated by movement, nature, and the street games of Bucharest. Born on March 9, 1907, on Mântuleasa Street, young Eliade discovered in the urban landscape a world full of charm and freedom. Early 20th-century Bucharest, with its alleys full of children and open fields echoing with laughter, offered him the perfect setting for his first adventures.

Childhood on Mântuleasa Street and the first games of freedom

In those days, sport was not an institutionalized activity but a joyful expression of life itself. Along with his neighborhood friends, Eliade played oina, the traditional Romanian bat-and-ball game requiring speed, precision, and teamwork. In his autobiographical work The Novel of the Nearsighted Adolescent, the author recalls how he “batted the oina ball on Mântuleasa Street” and how, in winter, he went sledding “until my feet were frozen” on the hill near the Metropolitan Church.

These memories were more than simple childhood anecdotes; they were formative experiences. For Eliade, play meant discipline, friendship, and courage—the first lessons in endurance and solidarity, values that would accompany him throughout his life.

The scout who conquered the mountains

As a teenager, Mircea Eliade joined the scouts, where he discovered a new dimension of adventure: mountain hiking. Equipped with backpacks, tents, and compasses, he and his fellow scouts spent days trekking through the Carpathians, sleeping under the open sky and learning survival and navigation skills. Eliade explored Piatra Craiului, the Bicaz Gorges, and other wild regions, experiencing the fatigue, cold, and silence of the mountains.

In a later interview, he admitted that these mountain experiences taught him not only physical courage but also contemplation—a way of understanding both nature and the human spirit. For the young philosopher in the making, the mountain became a place of initiation, a temple where the strength of the body met the depth of the soul.

The scouts’ expeditions helped him cultivate moral rigor and self-discipline, shaping his intellectual destiny. In a sense, every mountain journey foreshadowed his later spiritual explorations—an early preparation for the long path that would eventually take him to India.

Eliade on the Danube: the adventurer with the “Hai-hui” boat

If the mountains taught him contemplation, the Danube offered him the taste of pure freedom. At a time when Bucharest’s youth dreamed of great expeditions, Mircea Eliade and a group of friends designed and built a small sailboat, aptly named Hai-hui (“Wanderer”). With it, they embarked on a daring journey down the Danube, from Tulcea to Constanța.

The capricious winds of the Black Sea, the river’s strong currents, and nights spent on unknown shores tested their courage and ingenuity. But for Eliade, the experience became more than an adventure—it was a lesson in solidarity, adaptability, and teamwork.

He later recounted this episode in a collection of essays titled Oceanography, where he blended philosophical reflection with natural observation. For the young writer, the journey on Hai-hui became a metaphor for existence itself: life as a risky voyage in which courage and companionship keep one afloat.

The professor who taught the psychology of sport

After returning from India in 1933, where he had earned a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Calcutta, Eliade was appointed professor of psychology at the institution training future physical education teachers—today’s National University of Physical Education and Sports in Bucharest.

There, he contributed to shaping a new generation of educators, emphasizing the psychological dimension of athletic training. For Eliade, sport was not merely a physical pursuit but an exercise of the spirit—a path toward self-knowledge and inner balance.

He spoke to his students about the relationship between willpower and effort, about the mind’s ability to master the body, and about the symbolic meaning of competition as a form of self-transcendence. This holistic perspective—uniting body, mind, and spirit—became one of his intellectual trademarks.

Sport and literature: reflections on struggle, discipline, and play

Eliade’s passion for movement and competition also found its way into his literary works. In the short story General’s Uniforms, he references the game of chess, transforming it into a metaphor for life’s strategies—a confrontation between order and chaos, reason and instinct.

In The Captain’s Daughter, he highlights the educational virtues of boxing, viewing it as a discipline that strengthens character and prepares individuals for the challenges of modern life. Meanwhile, in the essay Apology for Décor and the story The Bridge, tennis becomes a symbol of human dynamism and the tension between control and unpredictability.

For Eliade, sport was a bridge between the physical and the spiritual. In every athletic endeavor he saw an allegory of inner struggle, of the effort to know and surpass oneself. This view fits perfectly within his broader philosophical system, where play, competition, and ritual carry sacred meaning.

Friends, mentors, and encyclopedic influences

Throughout his life, Eliade was surrounded by brilliant minds: Emil Cioran, Eugène Ionesco, and Mircea Vulcănescu. In the Paris of exile, these Romanian intellectuals spent long evenings debating philosophy, art, and religion, yet also sharing laughter and nostalgia.

Eliade’s passion for encyclopedic knowledge made him admire figures like Nicolae Iorga and Bogdan Petriceicu Hașdeu, scholars who combined theoretical depth with practical experience.

This duality of idea and action inspired Eliade to seek more than books or classrooms: he sought to live knowledge, to embody it.

Thus, the philosopher became simultaneously an explorer and a teacher, a sportsman and a contemplative thinker.

Personal tragedies and the strength of the spirit

Beyond his adventures and intellectual triumphs, Mircea Eliade’s life was marked by profound suffering. His first wife, Nina Mareș, died of cancer while they were living in Portugal, leaving him devastated. His second wife, Christinel Cotescu, remained a loyal companion until the end of his life.

Eliade also suffered two major losses of his personal library: once in Romania, when he entrusted it to a friend before leaving the country, and again in Chicago, where a fire destroyed his entire archive. These tragedies did not break him; they fueled his determination to rebuild, to continue writing and thinking.

One of Eliade’s defining traits was his extreme self-discipline. As a high-school student, he experimented with reducing his sleep hours to gain more time for study—eventually sleeping only four hours a night. The strain caused him to faint one day, forcing him to abandon the regimen. Yet the experience convinced him that the will could reshape the limits of the body.

The seeker of the absolute

Eliade’s thirst for knowledge had no boundaries. During his studies, he wrote to major philosophers and historians of religion around the world, requesting books and publications, which he later donated to his faculty library. This generous intellectual curiosity became one of his defining characteristics.

Part of his time in India remains shrouded in mystery. Some claim he spent a period in the Himalayas among monks, practicing meditative and shamanic techniques. Although never officially confirmed, this legend contributed to the aura of Eliade as a spiritual explorer—forever searching for the essence of human experience.

The legacy of a complete spirit

Mircea Eliade was not merely a philosopher or a historian of religions. He was a man of action, of direct experience, of movement and vitality. From the boy who played oina on Mântuleasa Street to the young man climbing the Carpathians and sailing on the Danube, and later the professor teaching sports psychology, Eliade’s life was a testament to courage, balance, and dedication.

Sport, nature, and adventure completed his theoretical thinking, offering him a profoundly human perspective. He understood that the spirit cannot rise without the strength of the body, and that true culture lies in the harmony between meditation and motion.

Thus, the nearsighted teenager of Bucharest became a giant of universal culture—a man for whom every step, every wave, and every game were exercises in freedom.

We also recommend: Tudor Arghezi and the 11 professions. What the great poet worked at before becoming a legend of Romanian literature