Bucharest had its first coffeehouse 360 years ago: the Janissary Haime, the “wine of the Orient,” and an everlasting story

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

For millions of Romanians today, the day begins with a hot cup of coffee. Yet behind this ordinary ritual lies a fascinating history: the arrival of coffee in Bucharest more than three and a half centuries ago. The first documented coffeehouse in Wallachia’s capital opened in 1667, founded by a Turkish Janissary named Haime.

His establishment was strategically located near what would later become Șerban-Vodă Inn, a bustling crossroads where merchants, soldiers, Ottoman travelers, and curious locals gathered. The novelty spread quickly, and coffee was soon nicknamed the “wine of the Orient”—a title that emphasized its stimulating effects and its exotic allure.

What a coffeehouse meant in the 17th century

The word “coffeehouse” comes from the Turkish kahve-hane, meaning “house of coffee” or “public place where coffee is consumed.”

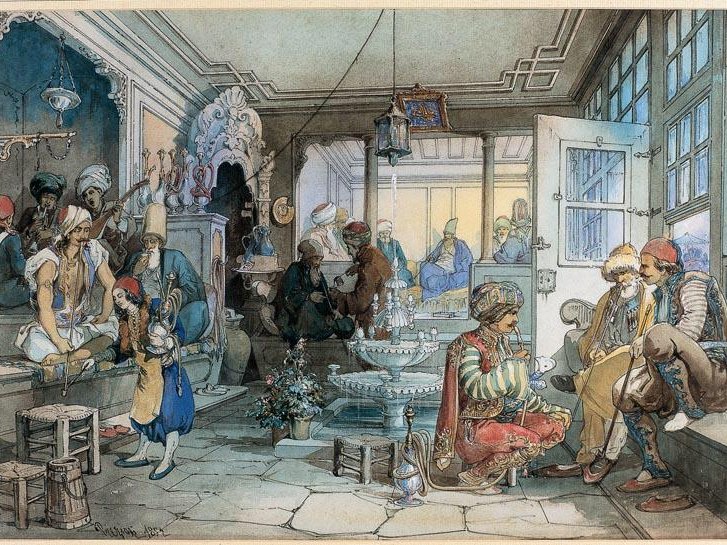

In the Ottoman Empire, such places were far more than venues for drinking; they were social institutions. People came there to play backgammon and dice, smoke pipes, discuss literature, religion, and politics.

It is very likely that Haime’s coffeehouse followed the same model. The air was filled with the scent of roasted beans and thick pipe smoke, while customers gathered to socialize, exchange news, or simply pass time in a lively atmosphere. Thus, the establishment became a small Oriental enclave in the heart of Bucharest.

Coffee at the princely court

Interest in this beverage did not remain limited to merchants or the Ottoman community living in the capital. Records show that coffee was also appreciated at the Princely Court of Bucharest.

In 1696, the treasury accounts of Prince Constantin Brâncoveanu recorded the purchase of about 19 kilograms of coffee from Ianachi Clucer, intended for the “prince’s pantry.”

Moreover, at the princely court there was even a dedicated official known as the “vel-cafegiu domnesc,” or chief coffee maker. His sole duty was to prepare the beverage for the prince and ensure its quality.

Coffee thus quickly became both a symbol of refinement and a marker of social prestige, consumed not only by ordinary townsfolk but also by the country’s political elite.

Turkish-style coffeehouses and their unique atmosphere

During the 18th century, Bucharest’s coffeehouses remained strongly shaped by the Ottoman model. They proliferated especially in commercial districts and along Podul Beilicului (today’s Șerban-Vodă Avenue), a route frequented by traders and soldiers from across the empire.

The atmosphere was typically Oriental: low tables, brightly woven carpets, thick pipe smoke, and the rich aroma of freshly brewed coffee. These coffeehouses also became places where important, sometimes uncomfortable, topics were debated.

A regulation issued in 1782 expressly banned “political discussions” in Bucharest’s coffeehouses, a sign that such venues had become forums for freely circulating ideas, including those critical of Ottoman rule.

Places of ideas and change

The authorities’ fear of coffeehouse gatherings clearly shows that these venues were not just sites of leisure. They attracted people from diverse backgrounds—merchants, students, intellectuals, and civil servants—who exchanged opinions and debated progressive ideas.

It is very likely that some of the earliest revolutionary and nationalist thoughts in Wallachia circulated precisely in these coffeehouses, later influencing the political evolution of the region.

In this way, coffeehouses contributed indirectly to the shaping of collective consciousness and to the emergence of an intellectual elite increasingly connected with European currents.

The rise of “European” coffeehouses

The 19th century brought about a significant shift. As Bucharest forged closer ties with Europe, the Ottoman-style coffeehouse began to be replaced by the Western model.

More spacious establishments appeared, furnished with elegant tables and chairs, large mirrors, and even billiard tables. These “European” coffeehouses soon became favorite haunts of the city’s bohemian circles, writers, politicians, and artists.

One famous example was Fialkowski Coffeehouse, founded by a Polish émigré who had settled in Bucharest. Here, great literary and cultural figures such as Ion Luca Caragiale, Duiliu Zamfirescu, Alexandru Xenopol, George Sion, and Matei Millo met regularly.

The atmosphere was intellectually stimulating, a space for literary, social, and political debates. It was far more than a café; it was a laboratory of ideas.

The coffeehouses of Bucharest’s bohemian elite

Beyond Fialkowski, other legendary coffeehouses became genuine social institutions. Capșa Coffeehouse was the preferred venue of Bucharest’s high society, a symbol of luxury and refinement.

On Lipscani Street, Schreiber Coffeehouse was frequented by merchants and businessmen. Meanwhile, the “Național” on Doamnei Street and “Bristol” on Academiei Street attracted select clients from political and intellectual circles.

These places were true centers of social life, where elites gathered, business contacts were established, and the major issues of the day were discussed. Coffeehouses were thus inseparably linked to the cultural and political vibrancy of the city.

Decline and transformation after World War I

The golden era of Bucharest’s coffeehouses lasted until the outbreak of World War I. The war’s aftermath profoundly disrupted economic and social life, and many of these establishments never regained their former splendor.

Coffeehouses did not disappear, but they lost their status as hubs of culture and politics, becoming instead ordinary venues for casual consumption.

Even so, the tradition of coffee endured. Bucharest residents continued to begin their mornings with a steaming cup, and this custom remained a defining feature of urban life.

The legacy of coffeehouses in contemporary Bucharest

Today, in Romania’s capital, coffeehouses are once again in vogue. In the Old Town and along the city’s main boulevards, modern cafés echo the charm of their historic predecessors.

They have returned to being spaces of encounter, socialization, and the exchange of ideas—just as they were more than three centuries ago.

Although many historic coffeehouses have vanished, their influence is still present in the city’s urban culture. Coffee continues to symbolize dialogue, friendship, and the bohemian spirit that has long defined Bucharest.

A story that continues

The story of the coffeehouse opened by the Janissary Haime in 1667 is not merely a historical curiosity. It marks the beginning of a tradition that has shaped Bucharest’s social and cultural life for centuries. From the first cups poured under Ottoman arches to the modern cafés bustling with young people and tourists, the city’s bond with the “wine of the Orient” remains as strong as ever.

In truth, the history of Bucharest’s coffeehouses mirrors the history of the city itself: a story of transformations, foreign influences, and a perpetual desire for reinvention.

Today, anyone sipping coffee on a terrace in the Old Town unknowingly carries on a tradition that began more than 360 years ago—a timeless story of taste, culture, and community.

Also recommended Alternative coffee shops in Bucharest: creative experiences in your cup — and beyond