Tudor Arghezi and the 11 professions. What the great poet worked at before becoming a legend of Romanian literature

By Andreea Bisinicu

- Articles

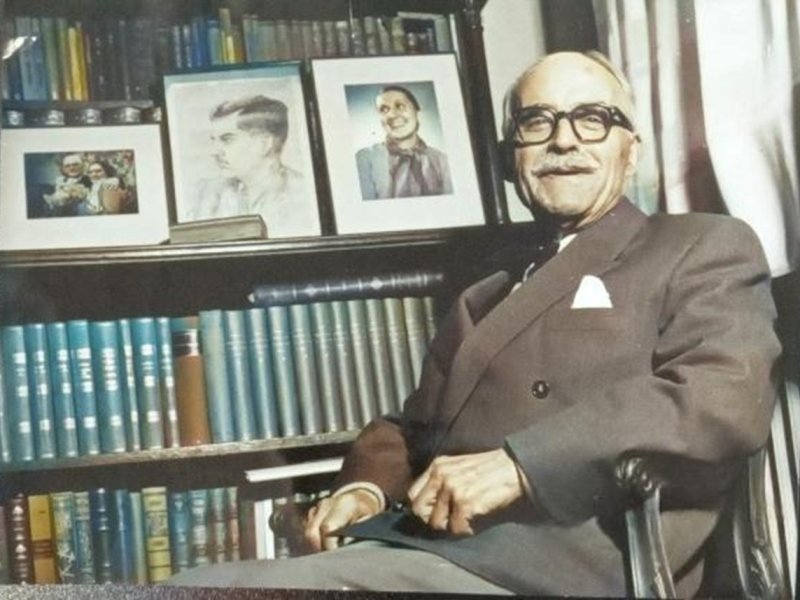

In 2025, 145 years passed since the birth of Tudor Arghezi, one of the most brilliant poets in the history of Romanian literature. Few, however, know about the multitude of professions the brilliant writer had throughout his life before becoming a legend. Tudor Arghezi's life was marked by an unceasing search – both spiritual and material. Behind his colossal work lies a complex destiny, filled with trials, reinventions, and radical transformations.

The man who knew to do it all

The great poet practiced, over the course of his existence, no fewer than eleven professions, from intellectual ones, such as journalist, to manual occupations – watchmaker, jeweler, or cherry seller. This diversity was not a whim, but a necessity imposed by the hardships of life and by a constantly restless spirit.

Tudor Arghezi, born Ion Nae Theodorescu on May 21, 1880, in Bucharest, came from a modest family, with origins in Gorj. Due to financial difficulties, he had to support himself from an early age. By the age of just 11, he was already earning his own living, and during school, he offered tutoring in order to continue his studies.

He attended the “Petrache Poenaru” Primary School, then the “Dimitrie Cantemir” Gymnasium, and the “Saint Sava” High School. However, he did not manage to complete his high school studies, leaving before taking the Baccalaureate.

At 16, he was employed as a custodian at an art exhibition, an experience that opened his horizons toward the artistic world. Two years later, he worked as a laboratory assistant at a sugar factory in Chitila, a modest job, but one that gave him his first contact with industrial work and the harsh realities of adult life.

The search for faith and the years spent at Cernica Monastery

One of the most unusual stages in Tudor Arghezi's life was his retreat to Cernica Monastery at just 19 years old. Deeply affected by the death of his beloved, the young poet sought refuge in faith, becoming the monk Iosif.

For four years, he led a monastic life, was ordained deacon, and brought to the Metropolis, where he worked as a secretary. In the same period, he was offered a position as conference referent for comparative religion at the Officers’ School.

Despite this closeness to the religious world, his soul remained troubled by questions and doubts. Arghezi did not find himself in the calm and order of monastic life. He was a free, critical, and nonconformist spirit. In 1905, he gave up monastic life and chose the path of exile, leaving the country to find meaning.

Years abroad: craftsmanship, study, and discoveries

After leaving the country, Arghezi first arrived in Paris, where he had a short relationship with Constanța Zissu, from which a son, Eliazar Lotar – a future photographer artist – was born. The poet recognized and supported him, even though his own life was in constant change.

From France, he moved to Switzerland, intending to attend the Catholic University of Fribourg, but the lack of a Baccalaureate diploma prevented him. Despite obstacles, Arghezi continued to educate himself, becoming a remarkable self-taught student.

To support himself, he learned the professions of jeweler and watchmaker, working in Swiss workshops, where he developed precision, patience, and an eye for detail. These qualities would later be reflected in the refinement of his poetic language, crafted with the same meticulousness as he would assemble the gears of a clock.

He lived for a while at the Cordeliers Monastery but refused to convert to Catholicism. Later, he traveled and worked in England and Italy, a period that profoundly shaped him, both intellectually and spiritually.

The five years spent abroad were essential to his development as a writer. Later, Arghezi would confess that the experiences lived among foreigners had taught him more about the human condition than any theology textbook.

Return to the country and affirmation as a journalist

In 1912, after a long absence, Tudor Arghezi returned to Romania. He did not have a university degree but had enormous life experience. He quickly established himself in the Romanian press, becoming a journalist and formidable pamphleteer. His collaborations with magazines such as Cronica, Viața Românească, and Facla imposed him as a strong and original voice.

Arghezi considered pamphlet writing a high form of journalistic expression, a weapon of intelligence and truth. His sharp, ironic, and lucid style made him a formidable adversary of hypocrisy and corruption. For him, the press was a moral platform, not a political one.

Over the years, he was also a printer, managing his own printing press at Mărțișor, where he sometimes published his writings. Manual work and intellectual work coexisted in his personality – the poet corrected his texts between two printed pages or two newspaper editions.

After three decades of searching and trials, in 1927, at the age of 47, Arghezi published his first volume of poetry, “Cuvinte potrivite” (“Fitting Words”), which definitively established him in Romanian literature. Critics would call him “the most important Romanian poet since Eminescu,” and the public discovered him as a unique voice – a craftsman of words, capable of transforming daily life into pure poetry.

The pamphlet “Baroane” and confrontation with history

During World War II, Arghezi faced a new conflict – this time with Nazi authorities. The publication of the pamphlet “Baroane”, a sharp text against the German ambassador, led to his arrest and detention at Târgu Jiu. The poet narrowly escaped being sent to a German camp or even execution ordered by the Gestapo.

After the war, with the establishment of the communist regime, Arghezi was once again banned and marginalized. In 1948, in the newspaper Scânteia, a denigrating article titled “The Poetry of Putrefaction or the Putrefaction of Poetry” appeared, discrediting his entire work. His printing press at Mărțișor was devastated, and his house threatened with confiscation.

To survive, the Arghezi family began selling cherries from the garden at Mărțișor. The gesture became a symbol of dignity and resistance through labor, a striking image of the poet who, deprived of freedom, earned his living with his own hands.

Rehabilitation and the poet’s final years

After years of forced silence, in 1952, Tudor Arghezi was gradually rehabilitated, at the initiative of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. However, this return to the public scene was accompanied by compromises.

The poet was obliged to publish articles and texts favorable to the regime, yet he did so subtly, preserving his dignity and characteristic irony.

In 1960, on his 80th birthday, Arghezi was celebrated as a national poet, and five years later, at 85, he was once again honored by the Writers’ Union and the Romanian Academy.

He died on July 14, 1967, being buried with national honors. His death closed an exceptional life, in which the destiny of a great poet intersected with the major upheavals of the 20th century – from wars and exile to censorship and glory.

The 11 professions – a mirror of a living conscience

Those who only know Tudor Arghezi’s literary work might be surprised by the complexity of his biography. Behind the poet stands a man who traversed eras, regimes, and continents, who knew hunger, exile, faith, and glory. He was laboratory assistant, custodian, monk, watchmaker, jeweler, self-taught student, journalist, pamphleteer, printer, political detainee, and cherry seller.

Each of these occupations represented a stage in the formation of his moral and artistic consciousness. From monastic life, he learned introspection and patience; from Swiss craftsmanship, precision and rigor; from journalism, the power of words; from exile, freedom of spirit; from suffering, dignity.

Tudor Arghezi was not only a great poet but a man of his time, a seeker of meaning and a craftsman of existence. His eleven professions are not mere occupations but chapters of an initiatory biography, in which the man and the artist built each other.

Thus, from the poor child of 19th-century Bucharest rose one of the greatest creators of the Romanian language, a poet who transformed labor, faith, and suffering into art. Arghezi demonstrated that talent is not a static gift but the fruit of a life lived intensely, between pen and anvil, between printing press and the cherry garden at Mărțișor.

Behind each of his verses lies the experience of a complete human being, who knew all faces of life. And this human strength, acquired through his eleven professions, was the foundation on which the legend of Tudor Arghezi – the poet who made words a form of freedom – was built.

We also recommend: The most unique “Mărțișor” in Bucharest. The Tudor Arghezi Memorial House, in whose courtyard the poet’s entire family is buried