“The Floods” of the Capital | ApaNova Director: “I haven’t seen anyone boating through Bucharest.”

By Bucharest Team

- NEWS

- 29 JUN 25

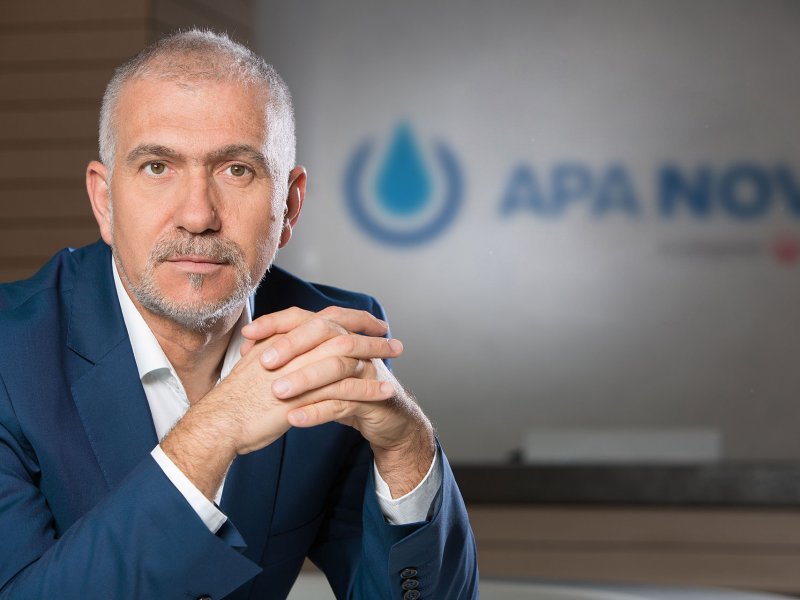

Shortly after the editorial “The violent storm in Bucharest is called ApaNova” was published, the company’s leadership contacted Buletin de București to arrange a technical discussion and a final interview with the general director of Veolia Romania, Mădălin Mihailovici, which we conducted in mid-June. We chose to publish the editorial outcome in full, given the complexity of the topic. We note that this article is strictly in the public interest and is not part of any paid advertising or “advertorial” services.

The capital is increasingly facing extreme weather phenomena, with torrential rains testing the city’s infrastructure and, implicitly, the sewage system managed by the concessionaire Apa Nova.

Buletin de București spoke with the general director of Veolia Romania and ApaNova Bucharest, Mădălin Mihailovici, analyzing how the company is coping with these challenges, what critical and delayed investments are needed, and what bureaucratic obstacles are slowing down the modernization of Bucharest’s sewage system.

Details in the interview below include “spot rains” and pressure on the system, the “smart wastewater tunnel under Dâmbovița,” future massive underground reservoirs planned under Izvor, Opera, and Tineretului parks to prevent flooding in “bucket zones” of Bucharest, and how the city is kept “afloat” during flood peaks.

Reporter: Bucharest is increasingly experiencing extreme weather, especially in summer—heavy rains in short periods that put pressure on the sewage network. How does Apa Nova evaluate this situation, and what developments do you anticipate?

Mădălin Mihailovici, General Director of ApaNova Bucharest:

These are manifestations of profound climate change, and the intensity of the phenomena is increasing. In May, we had record rainfall—203% above the multiannual average. We accumulated in less than 10 days what we normally get in a full year for that period.

The latest rainfall, at the beginning of June, was extremely intense and occurred in a record short time—under two hours. I want to remind you that on June 13–14, 2024, there was a similar event, but it lasted 3 hours and 20 minutes. The recent one was under two hours. The rainfall on Pentecost Monday introduced 4.3 million cubic meters of water into Bucharest’s sewer system—including water collected from surrounding metropolitan areas like Ilfov. For comparison, the Lacul Morii reservoir holds 10 million cubic meters at normal levels—so in just two hours, we processed half of that.

Lacul Morii is the main accumulation lake on the Dâmbovița River and plays a key role in flood protection. Built starting in 1985, its purpose was to retain Dâmbovița waters and prevent flash floods. There are concerns about the condition of the dam and drainage system, with reports indicating maintenance and repair needs. If the dam failed, parts of the city could flood, although the probability of such an event is considered minimal.

Additionally, this rain had an average of 45 liters per square meter over two hours, exceeding the 2024 event’s 39 liters over 3 hours and 20 minutes. In 2025, some areas reached 70 liters per square meter on average, and for a few minutes, intensities spiked to 120 liters per square meter.

Reporter: These are the so-called “spot rains.” How much pressure did they put on the capital’s sewer system?

M.M.: These were extremely intense rains. I’ve heard people refer to the Pentecost Monday rain as a “once-in-a-100-years event.” The correct term is “exceedance probability.” That doesn’t mean it only happens once in 100 years. There are statistical curves in hydrology—intensity-frequency curves. Statistically, such an event could be exceeded once every 100 years, but it could also happen 3–4 times in one year. So these phenomena are growing in intensity.

“Spot rain” isn’t a standard meteorological term. It refers to very heavy, highly localized downpours that affect a limited area.

This recent rain lasted only two hours, and by the next morning, the sewer system was back to “normal.”

Reporter: Do you believe the sewage system functioned properly?

M.M.: I completely disagree with the idea that the system didn’t work. I didn’t see anyone boating through Bucharest. After two hours, traffic was flowing again. Yes, we know there are low-lying areas. We’re working on those, we’re making investments. But before you can build anything, you need designs, permits, and land purchases. We invest every year, and our investments are made from the water tariff. And I want to emphasize that Apa Nova Bucharest, Apa Nova Ploiești, and all Veolia water and sewerage services in Romania have the lowest tariffs—and still, we manage to make major investments.

Reporter: Based on predictions and probabilities, what investments have you planned in advance for such events?

M.M.: For high-intensity phenomena, the key is to “cut the flood peak.” In hydraulics, this is called Peak Maximum Flow. If we can shave the top off that peak, we can keep the sewer and drainage systems from going into overpressure.

If we can release the flood peak via the Dâmbovița River and wait for the levels to drop, the remaining water can go into the sewer system. That’s exactly what we’re doing with modifications at the wastewater tunnel outlet. We’ve essentially created “pockets” to help control flood peaks.

Reporter: Would more precise and timely forecasts help you better prepare the system?

M.M.: The system is always prepared. We have large collector channels on both sides of the Dâmbovița and the main wastewater tunnel underneath the riverbed. These are the mainline channels. For example, one is 27 kilometers long, going from Mogoșoaia to the hydraulic node at Popești-Leordeni. The A3 collector serves sectors 6, 5, and 4 and stretches 23 kilometers. Think of it like a highway section.

The wastewater tunnel under the Dâmbovița is the central collector system for all wastewater in Bucharest. Located beneath the riverbed, this essential infrastructure collects most of the city’s sewage and stormwater, transporting it to the Glina Treatment Plant before discharge. The tunnel's longitudinal path is over 17 km long, and the total length of the entire underground system exceeds 44 km, including various semi-tunnels.

Read more on Buletin de București.