Where does the name of Lipscani Street come from: the great street, merchants and Bucharest’s elite

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

In the heart of old Bucharest, Lipscani Street has always had a special place. Documented as early as 1589, it was then known as the “Great Street” (Ulița Mare). Located next to the Old Princely Court – the residence built by Vlad Țepeș – the street quickly became a key point in the city’s economic life. Merchants, craftsmen and travelers met here daily, turning it into a lively and bustling place.

The first mentions and the role of the great street

The organization of guilds gave Lipscani a distinctive identity. Each craft had its own section of the street: furriers on Blănari Street, saddle makers on Șelari, cap makers on Șepcari, money changers on Zarafi, while Bulgarian merchants from Gabrovo settled on Gabroveni.

This distribution brought both order and diversity, concentrating in one area the essential crafts of the city.

The origin of the name Lipscani

The name that made the street famous came from the connection between Romanian merchants and Leipzig, the German city known at the time as “Lipsca.” Merchants from the Romanian lands, as well as Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs, often traveled there to buy high-quality goods. Over time, the term “lipscan” came to designate merchants who traded in Western products. When these merchants concentrated on the Great Street, the name naturally took root: Lipscani.

This name is not just a toponym, but also a testimony of Bucharest’s openness to Europe. Lipscani thus became the symbol of a capital tying its economic destiny to Western markets.

Inns: commercial and social spaces

For the merchants and travelers of the time, the inns on Lipscani were indispensable. They provided lodging, trading areas, and storage spaces. Among the most famous were:

· Hanul Șerban Vodă, inaugurated in 1686 by Prince Șerban Cantacuzino. It housed the city’s first pharmacy, as well as the City Council, the forerunner of the modern City Hall. Though it survived fires and earthquakes, it was demolished in 1885 to make way for the headquarters of the National Bank of Romania.

· Hanul Zlătari, built around the church of the same name. It was connected to the guild of goldsmiths who worked with gold and silver.

· Hanul Gabroveni, constructed in 1739 and frequented by Bulgarian merchants, but also by foreign diplomats, being famous for its quality rooms.

The inns were, at the same time, spaces for social and political encounters. They were part of the city’s public life, not just its economy.

Architectural transformations

Lipscani evolved not only through trade, but also through architecture. Initially, the buildings were modest, made of wood and covered with shingles. However, the frequency of fires forced a transition to brick structures with Turkish-style tile roofs, and later with tin.

The street pavement also went through transformations: from beaten earth to stone, then to wooden beams, and eventually to wooden blocks. Some sections of this pavement lasted until the First World War, a silent witness of successive modernizations.

Cosmopolitan Lipscani in the 19th century

In the 19th century, the street reached its commercial and cultural peak. Lipscani became a cosmopolitan hub, where Western and Oriental influences blended harmoniously. Shops sold everything from fine textiles and jewelry to footwear and luxury items.

This was also the place where the first banks, the first bookstores and important publishing houses appeared, as well as shops with a distinctly Western flair. It was not only a shopping street but also a true promenade, where boyars, merchants, and artists met daily.

Names such as Tudor Hagi Tudorache, Nicolae Chiru, Stancu R. Becheanu or Gheorghe Coemgiopolu left their mark on Bucharest’s trade, contributing to Lipscani’s transformation into a center of influence.

Decline and changes during the communist period

After the Second World War, and especially during the communist period, Lipscani lost much of its charm. Historic buildings were neglected, while traditional commerce was replaced by standardized state-run shops. Yet the street still remained a point of attraction for Bucharest residents.

Stores such as “Macul Roșu” (The Red Poppy), “Bizonul” (The Bison), “Porțelanul” (The Porcelain) or “Trusoul” (The Trousseau) were very popular, offering a variety of products in a context of limited supply. The George Coșbuc Bookstore also operated here, continuing the tradition of the bookstore inaugurated in 1854 on the same spot – one of the first in Bucharest.

The rebirth of Lipscani after 1989

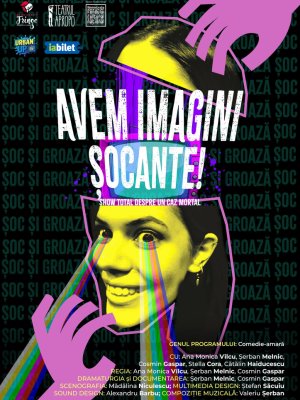

The changes after 1989 radically transformed the area. The restoration of historic buildings, the revival of its heritage, and the opening of numerous restaurants, bars, galleries, and theaters returned Lipscani to its status as the center of Bucharest’s life.

Today, the street is not only a place for shopping or entertainment but also a cultural symbol. Tourists see it as a must-visit attraction, while locals rediscover it with joy, as a bridge between the city’s history and its dynamic present.

Lipscani – a symbol of Bucharest’s spirit

From the merchants’ street supplied from Leipzig, to the cosmopolitan hub of the 19th century, through the communist decline and the post-1989 rebirth, Lipscani remains a landmark of the capital. Its history reflects, in concentrated form, the history of Bucharest itself: full of transformations, contradictions, but also with an extraordinary capacity for reinvention.

Today, walking down Lipscani, one can feel the pulse of the old guilds, the echoes of boyars’ footsteps, and the energy of today’s generations that turn the street into the beating heart of urban life.

It is, without a doubt, a place where past and present coexist, revealing the true essence of Bucharest’s spirit.