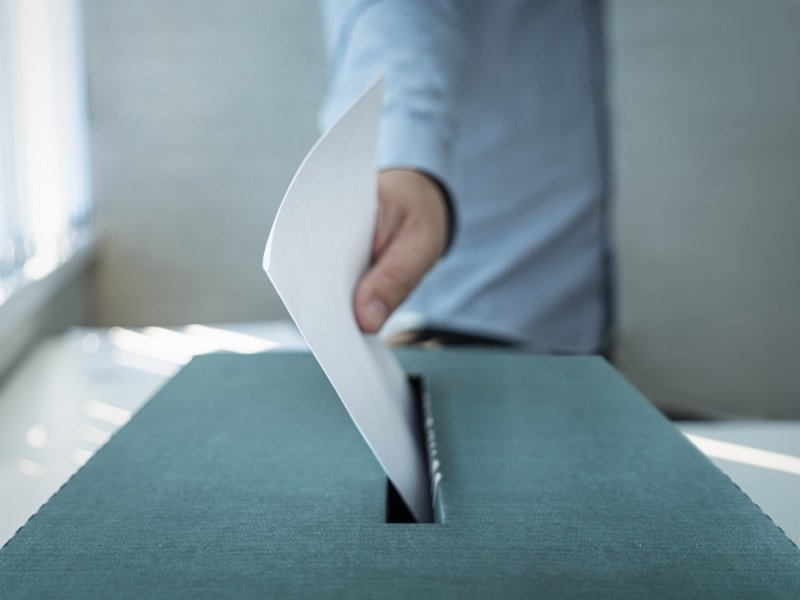

Very low voter turnout in Bucharest: a symptom of a broken relationship between the administration and the electorate

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

Voter turnout of roughly 32–33% in the election for Bucharest’s City Hall is not a one-off deviation but the confirmation of a trend that has solidified over the past decade. Bucharest — a city of more than two million residents with a complex socio-demographic structure — no longer responds to electoral cycles through mobilization but through withdrawal. Understanding this phenomenon requires an analysis that goes beyond convenient explanations and looks instead at the structural causes.

1. An opaque administrative architecture that dilutes responsibility

The Capital operates within a fragmented institutional system: the General City Hall, six district mayors, subordinate administrations, agencies, municipal companies — each with overlapping competencies. For the average resident, it is increasingly unclear who is responsible for road quality, green spaces, district heating, or sanitation. Without a clearly identifiable decision-making center, the vote loses its perceived value: citizens can no longer associate a political decision with a concrete outcome.

2. The absence of visible urban transformation

The city’s fundamental problems — traffic, district heating, pollution, urban incoherence — remain unchanged year after year, regardless of who is in office. This long-term continuity of dysfunction reinforces the idea that political turnover does not produce structural improvements. Without unmistakable demonstrations of administrative competence, more and more voters conclude that voting is symbolic, not an effective corrective tool.

3. An electoral campaign without tension, debate, or defining themes

The Bucharest elections unfolded under an inert campaign, devoid of real confrontation and lacking projects capable of engaging an urban electorate that expects clarity and relevance. Candidate communication was technical and unilateral, without articulating recognizable stakes. In the absence of a clear political conflict or an urgent theme, participation inevitably declines.

4. An urban electorate exhausted by repeated promises and sterile administrative cycles

For thirty years, Bucharest has been locked in a strained relationship with its own administration: projects begun and abandoned, institutional experiments, politically redirected budgets, reforms announced but never implemented. This history produces accumulated disillusionment, not just episodic distrust. Voters no longer wait for change; instead, they avoid disappointment through non-participation.

5. The lack of candidates capable of mobilizing beyond their natural base

No candidate managed to propose a genuinely transformative theme or spark cross-camp mobilization. Without a political figure perceived as a rupture from past administrations, voter behaviour remains minimalist.

6. Educated and professionally active segments — those that traditionally raise turnout — are withdrawing from the process

A significant portion of the population with higher educational and economic capital no longer sees local elections as an effective instrument of influence. This is not apathy but a rational decision to withdraw: without trust in institutional mechanisms, participation becomes, for many, a gesture without impact.

7. Bucharest’s demographic structure does not favour electoral mobilization

The city has a volatile electorate, weakly anchored in community networks and marked by diffuse political identities. Additionally, groups that in other regions drive higher turnout — residents depending on local patronage networks — are far less present here.

Sociological context: Bucharest and its electoral specificities

To grasp the scale of abstention, Bucharest must be viewed comparatively. Large European capitals with mobile, professionalised, socially fragmented populations tend to have lower turnout in local elections, yet Bucharest amplifies this pattern for internal reasons. Its social structure is shaped by continuous mobility, weak community attachment, and a high proportion of residents who do not project their long-term future in the city. This erodes the motivation to vote and weakens the sense of civic responsibility.

Bucharest also concentrates a significant share of residents with unstable work schedules: freelancers, intra-metropolitan commuters, workers in highly mobile professional fields. For many of them, local politics is not a fixed reference point. Their relationship with the city is functional rather than identity-based, which naturally depresses turnout.

Historical evolution of turnout: a slow but steady decline

Across the last five local election cycles, turnout in Bucharest has followed a clear downward trajectory, regardless of the national political climate. Paradoxically, periods of political polarization — which in other cities can boost participation — generate, in Bucharest, only further fragmentation.

The explanation lies in the fact that Bucharest does not vote on the basis of stable political identities but reacts instead to perceived administrative performance. When an administration is seen as ineffective, the response is not mobilization against it, but a retreat into abstention.

Gradually, local voting has been reinterpreted by residents as an act with limited value, producing effects far below expectations. This persistent perception erodes participation even in relatively competitive electoral contexts.

An electorate that reacts to crisis, not to governance

A distinct feature of Bucharest’s electorate is that turnout rises only in conditions of explicit crisis — major scandals, institutional collapse, intense political conflict. In their absence, voters follow an apathetic pattern, shaped by a weakening emotional and cognitive connection to the city and by the belief that local administration changes slowly regardless of who is mayor.

This crisis-only reactivity creates a self-reinforcing cycle: politicians under-invest in coherent administrative communication, voters do not perceive improvements, abstention grows, and administrative legitimacy declines.

Low turnout in Bucharest is not just a statistic but a marker of a long-term fracture between the city and its residents. It stems from the intersection of institutional confusion, failure to deliver, the absence of real electoral competition, social fragmentation, and the erosion of trust in public mechanisms.

Until the city manages to offer results and predictability, and until administration becomes intelligible to its citizens, abstention will continue to be the rule rather than the exception.

Also recommended UPDATE – PARTIAL LOCAL ELECTIONS – Ciprian Ciucu, winner of the Bucharest election with 36.16% / The gap compared to the runner-up exceeds 83,000 votes