The Royal Palace in Bucharest, between monarchy and art. How it became the most beautiful museum in the Capital

By Andreea Bisinicu

- Articles

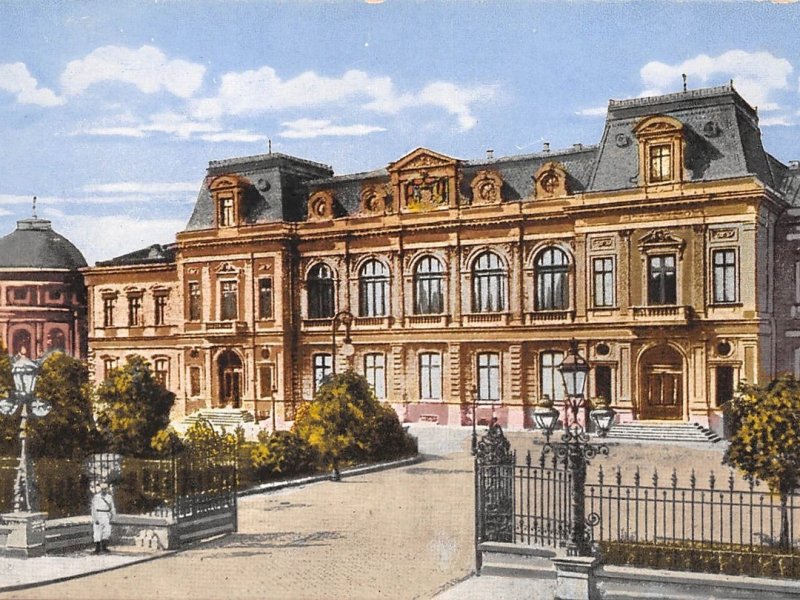

Walking along Calea Victoriei, one of the most bohemian and elegant boulevards in Bucharest, your eyes are inevitably drawn to the imposing building that dominates the area: the Royal Palace. This monumental construction, with a history spanning more than two centuries, is a symbol of change, of Romanian royalty, and of the art that shaped the architectural identity of the capital.

19th-century Bucharest and the need for representation

Bucharest, which became the capital in 1659, went through numerous stages of glory, stagnation, and decline. The 19th century was undoubtedly the century of radical transformations.

Under the influence of the Commission for the Beautification and Modernization of the City, founded as early as 1860, the capital experienced an accelerated process of Europeanization: the introduction of street lighting, the systematization of streets, the first sewerage networks, road paving, and later, the arrival of the telephone.

Bucharest sought to align itself with the great European capitals, and this drive for modernization also required a proper symbol of power – a royal palace.

From the Golescu House to the Princely Palace

The land on which the Royal Palace now stands once looked completely different. In the 18th century, the Podul Mogoșoaiei area (today’s Calea Victoriei) was a peripheral, insignificant zone.

The first steps toward building a future palace were taken in 1757, when the merchant Voico Fiştu built a house that he later left to Crețulescu Monastery. Over time, through exchanges and successive sales, the property came into the possession of the Golescu family.

Dinicu Golescu, an enlightened boyar concerned with progress, expanded the house, turning it into one of the most imposing residences on Podul Mogoșoaiei.

After his death, his heirs sold the property to the Administrative Council, and in 1837, Prince Dimitrie Ghica transformed the house into the Princely Palace, a place of representation and authority.

Later, the palace passed to Barbu Știrbei and then to Alexandru Ioan Cuza, who added an extra floor and turned the residence into a symbol of the Union of the Principalities.

Carol I and the dream of a European palace

The arrival of Carol I on the throne of Romania brought with it the desire to transform Bucharest into a capital worthy of modern Europe. The king, accustomed to the elegance of Western palaces, could not accept that his official residence should be a modified boyar house.

In his memoirs, Carol I ironically described the modest and neglected appearance of the old palace, located near a filthy square where “pigs wallowed in the mud.”

Thus, in 1882, the project for a new Royal Palace was entrusted to the French architect Paul Gottereau, known for his eclectic and refined style.

The new building comprised three sections: Cuza’s former residence, the central wing – which housed the Throne Hall and reception rooms – and a new right wing intended for the guard and for accommodating official guests.

Carol I’s palace combined neo-classical influences with French eclecticism, fitting perfectly into the landscape of a capital eager to rival Paris or Vienna.

The 1926 fire and reconstruction

A dramatic episode marked the history of the Royal Palace on the night of December 7–8, 1926, when a devastating fire destroyed the central wing.

Protection works were carried out by architect Karel Liman and in 1927 King Ferdinand decided to rebuild the palace, bringing major improvements: a larger Throne Hall, a Hall of Festivities, and a Banquet Hall.

The modifications also included expanded spaces for distinguished guests, turning the palace into a true landmark of royal protocol.

The final stage of construction took place during the reign of King Carol II, who continued to modernize and extend the palace. Thus, the building gained the form we recognize today, a symbol of Romanian royalty and national prestige.

From royal residence to political headquarters

The abdication of King Michael I in 1947 radically changed the destiny of the Royal Palace. The building passed into state administration and became the headquarters of the Romanian Government.

During the communist regime, the palace lost its initial function, being adapted to political needs. In 1959, the rear of the building was converted into a conference hall for the Romanian Communist Party, taking advantage of its proximity to the Central Committee headquarters.

Despite these transformations, the Royal Palace remained a unique architectural landmark, an example of how local tradition blended with European influences.

The architecture of the Royal Palace

From an architectural perspective, the Royal Palace is considered the last great European example of a program of monarchical representation. Its style is the result of a double evolution: local – through continuity from Curtea de Argeș, Târgoviște, and Bucharest’s Old Princely Court – and continental, influenced by the models of newly established kingdoms such as Greece and Norway.

The main façade is remarkable for its use of the colossal Corinthian order, spread over two levels. The columns and pilasters give the building a monumental and balanced appearance, while symmetry is carefully maintained between the two wings – Crețulescu and Athenaeum.

Inside, the architecture is varied and richly decorated, from the reception hall with its coffered ceiling and massive columns, to the Florentine Hall, with its painted ceiling and elegant arches.

A spectacular feature is the Voivodes’ Staircase, which connects the entrance to the Throne Hall. Here, paired columns and a painted dome create a solemn space, enhanced by relief medallions depicting the most important rulers of Romanian history.

The Throne Hall, impressive in size and detail, covers almost 1,000 square meters with a height of 12 meters, decorated with Corinthian arcades and ornamental grilles.

The materials used – marble, stone, exotic wood, bronze, and gilded stuccoes – reflect the taste of the time for eclecticism and refinement. Numerous frescoes, paintings, and decorations were created by both Romanian and foreign artists, in styles ranging from academic to impressionist.

The Royal Palace as the National Museum of Art

After the fall of the communist regime, the Royal Palace was returned to culture. Today, the building houses the National Museum of Art of Romania, the most important institution of its kind in the country.

The sumptuous spaces, once reserved for royal balls and ceremonies, now display impressive collections: the National Gallery, with works by Grigorescu, Luchian, Aman, and Bălcescu, and the European Art Gallery, with masterpieces by great artists such as El Greco, Rembrandt, and Rubens.

The transformation of the palace into a museum did not simply preserve a historical building but revitalized it through culture. Visitors step not only into an art space but also into a place steeped in history, where the echoes of kings’ footsteps blend with the eternal beauty of painting and sculpture.

Between royalty and art

The Royal Palace in Bucharest is more than just a monumental building on Calea Victoriei. It is a symbol of national history, of transformation, and of the indissoluble bond between monarchy and culture.

From boyar residence to Princely Palace, from royal residence to political headquarters, and finally to museum, the building reflects the tumultuous path of modern Romania.

Today, when we enter its halls, we encounter not only artistic masterpieces but also a space where history breathes through every column and fresco.

The Royal Palace continues to bear witness to Bucharest’s ambition to rise to a European level and to the power of art to turn any wall into living memory.

We also recommend: Bucharest’s Calea Victoriei “breathes” history: the old Mogoșoaia Bridge was paved by Constantin Brâncoveanu with tree trunks