Captain Costache Chioru, the most corrupt policeman in the history of Bucharest: He tortured detainees until he obtained the “convenient confession”

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

The history of Bucharest hides characters who passed from reality straight into dark legend. Among them, few figures stirred as much fear, hatred, and revulsion as Captain Costache Chioru, the man who, for more than two decades, became the absolute symbol of abuse of power. For the people of Bucharest, his name turned into a synonym for terror, the whip, humiliation, and injustice.

The terror of old Bucharest

Historians, memoir writers, and leaders of the 1848 Revolution wrote about him. George Potra dedicated memorable pages to him in the volume From the Bucharest of Yesterday, while Nicolae Bălcescu mentioned him as one of the most sinister figures of the old regime.

Costache Chioru was not merely a violent policeman, but a true master of the streets, a man who “cut and hanged” in the capital, using his position for plunder, revenge, and fear.

The real figure, Costache Chihaia, nicknamed Chioru because he had lost one eye, quickly entered the urban folklore of the city. Although blind in one eye, contemporaries said that “with the other he saw like a vulture.” He came from a minor boyar family and knew how to climb the ladder of power through servility and cruelty.

George Potra recounts that elderly people of Bucharest still remembered, at the beginning of the 20th century, the terror inspired by his appearance. Merchants pulled down their shutters, residents of the outskirts let their dogs loose and watched from behind fences as his entourage passed. Only when the horses’ hooves faded into the distance did people breathe again, as if after a mortal danger.

The Agia’s dorobanți, instruments of terror

In 1824, Costache Chioru was appointed chief of the Agia’s dorobanți, the police force of Bucharest. This unit numbered about 50 men and was meant to maintain public order. In reality, under Chioru’s command, the dorobanți became a true urban terror squad.

For twenty years, he served under powerful boyars who led the city’s police, such as Manolache Florescu and Iancu Manu. Protected by them, Costache Chioru turned into the “whip of fire” of the authorities, the man sent to crush any sign of popular unrest.

A policeman rewarded for cruelty

Paradoxically, although the population hated him, the authorities valued him. In 1843, Chioru earned a monthly salary of 300 lei, a considerable amount at the time, and Prince Gheorghe Bibescu officially rewarded him for his “tireless activity” in fulfilling his exhausting duties.

The report came from the “Department of the Interior,” the equivalent of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. For the regime, Costache Chioru was the ideal policeman: merciless, unscrupulous, and willing to trample any law to preserve apparent order.

In reality, as George Potra wrote, he was nothing more than “a sinister type of brutal and greedy policeman,” who had turned his very name into a cry of terror.

Torture as a method of investigation

For Costache Chioru, the law was merely a pretext. Anyone who crossed him — thief or honest citizen alike — was thrown into the cellars of the Agia. There, beating was the standard investigative method. Detainees were tortured until they produced what Chioru called the “convenient confession.”

Truth did not matter, only usefulness. Many confessed to crimes they had never committed, simply to escape the torment. After extracting the confession, Chioru arbitrarily decided whether to send the victim to the salt mines or release him — usually in exchange for money.

Theft under the cover of the law

Costache Chioru increased his fortune through a perfectly organized system of robbery. When he caught a highway thief, he took all the gold coins and loot, then let him go free. When he entered a house under the pretext of a search, he “turned it upside down,” keeping whatever he found.

Alexandru Antemireanu, in the book Captain Costache, an Evocation from the Past, describes devastated homes, humiliated families, and goods that vanished without a trace. Bucharest residents knew that a visit from the dorobanți meant certain ruin.

The banning of the “geamala” and popular repression

Antemireanu recounts a famous episode: the banning of the traditional folk dance known as geamala, extremely popular in the city’s neighborhoods. The geamala was a gigantic female effigy, carried by a man hidden inside, dancing to the music of fiddlers.

One festive day, while people were joyfully dancing on Dealul Spirii, Costache Chioru stormed in with his dorobanți. What followed was a scene of unimaginable brutality: screams, curses, children trampled, faces slashed, backs bruised. The twelve-thonged whip struck indiscriminately, and no one dared protest.

Abuses, violated women, and orphaned children

Accounts from the time speak of a true reign of fear. Antemireanu writes of women and girls violated, of children left homeless while their parents died from the horrific tortures inflicted by Chioru’s men.

Costache Chioru abducted women he desired, took them to hidden houses, abused them, then released them under terrible threats to ensure silence. Many swore revenge, but none dared act.

The search of Cezar Bolliac’s house

The poet of the 1848 generation, Cezar Bolliac, left a direct testimony of Chioru’s methods. In 1839, he wrote that the captain “frankly raided my house.” Under the pretext of an order, the dorobanți confiscated all his books and papers and left without explanation.

Bolliac was considered dangerous to the regime, a young man “inclined toward rebellion,” and his home had become a meeting place for progressives. For Chioru, free thought alone was enough to justify repression.

His role in suppressing the 1848 Revolution

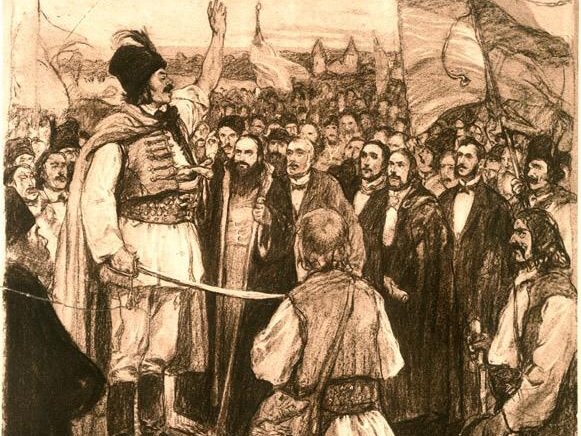

The peak of Costache Chioru’s cruelty came during the Revolution of 1848. When signs of agitation appeared in Bucharest, he received free rein to search, arrest, and intimidate.

On June 11, 1848, his dorobanți blocked the streets. Those shouting “Long live Freedom” were beaten and trampled. Chioru ran through the city like a madman, shouting threats meant to terrorize the population.

“I will braid my whip with Romanian skin”

According to George Potra, Captain Costache shouted in the streets that he would braid his whip with Romanian skin and paint his saddle with Romanian blood, so that people would remember what freedom meant when attempted there.

Nicolae Bălcescu also wrote that his appearance with the whip caused revolutionary banners to be torn down. After the suppression of the movement, Ottoman troops entered the city, bringing plunder and rape, followed again by the terror of Chioru’s dorobanți.

Praised by the authorities, hated by the people

While the city suffered, the authorities praised him. Boyar Iancu Manu publicly described him as “an elite police bloodhound,” a servant of rare energy and boundless devotion. This contrast perfectly illustrates the gulf between power and the people.

For Bucharest residents, Costache Chioru was the embodiment of evil. Mothers frightened their children with his name, and little ones hid in cellars when they heard he was coming.

Debts, greed, and endless corruption

Although he had a good salary, bonuses, and constant plunder, Chioru was always borrowing money that he never repaid. He took large sums from merchants, fur traders, and even a Prussian subject. He withheld the salaries of his subordinates for months, collecting the money himself.

Not even his former wife, Uța, escaped his greed. He tried to defraud her by demanding gold coins she did not owe.

His home, family, and final years

Until 1838, he lived in the house of his former wife in the neighborhood of the White Church of the Clothmakers. Later, he built a large home on Podul de Pământ, today’s Calea Plevnei. The house was spacious, richly furnished, with a vast garden and brackish water sweetened with sugar loaves to make it drinkable.

He married several times, but only with his last wife, Sița, did he have children: three sons and two daughters. He died old, peacefully, and was buried in the courtyard of Saint Constantine Church on Calea Plevnei.

The legacy of collective fear

Captain Costache Chioru left behind no laws, no institutions, no reforms. He left only fear. He became the symbol of the corrupt, violent, inhuman policeman — a figure that shows how easily authority can be transformed into an instrument of terror.

His story remains one of the darkest pages in the history of Bucharest, a lesson about what happens when power falls into the hands of a man without limits, without mercy, and without conscience.

We also recommend: General Ioan Emanoil Florescu, founder of the Romanian Army, has a street bearing his name in the center of Bucharest