Corso Café, the story of the favorite venue of writers and journalists in interwar Bucharest

By Andreea Bisinicu

- Articles

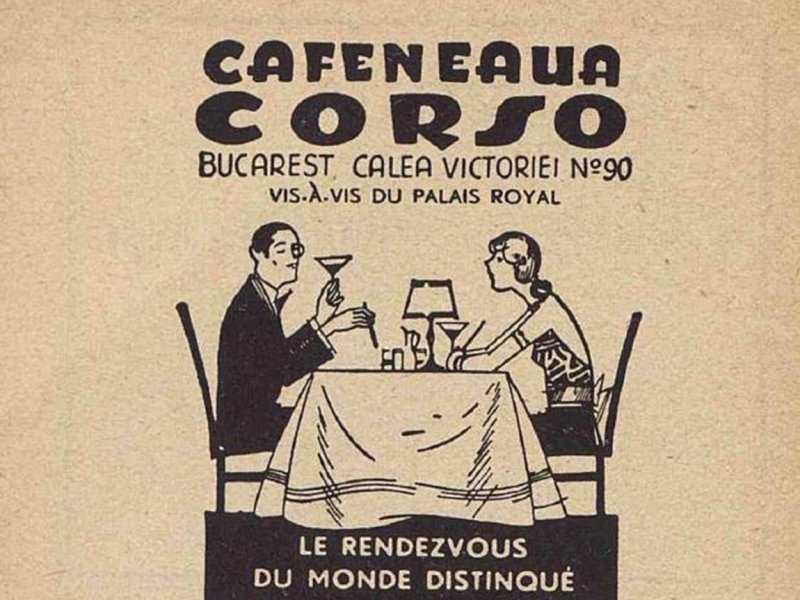

During the interwar period, Bucharest was living one of the most effervescent stages of its existence. The capital was nicknamed “Little Paris,” and Calea Victoriei had become the axis around which institutions, editorial offices, theaters, and famous cafés gravitated. Among them, Corso Café held a special place. Located opposite the Royal Palace and in the immediate proximity of the Athenaeum Garden, in the same building as the Romanian Jockey Club, Corso was not just an elegant venue, but a true laboratory of ideas.

A landmark of the literary bohemia on Calea Victoriei

Opened by Finkelstein, nicknamed by clients “the baron,” the café was conceived according to the Viennese model, with a refinement rarely encountered in Bucharest of those years. The furniture, the atmosphere, the impeccable service, and the selection of products turned Corso into a cosmopolitan space. It was the place where the aristocracy of spirit met the ambition of young writers, where the hurried journalist could sit at the same table with the philosopher concerned about the destiny of Europe.

Writer Vlaicu Bârna, in the memorial volume “Between Capșa and Corso,” described the venue as a sumptuous space, with tables framed in boxes upholstered in burgundy velvet, under a ceiling adorned with Murano lamps that suggested a starry sky. The large windows offered views either toward the Palace or toward the Athenaeum Garden. The entrance was made through a revolving door that led into a circular corridor, delimiting the tables along the walls from those in the center. Everything breathed order, elegance, and a discipline of conversation which, although animated, did not slip into vulgarity.

The writers’ table and the endless debates

Corso quickly became the preferred place of writers and journalists. In the downstairs hall, on the left side at the back of the room, was the famous table of the press and artists. Here one could frequently meet Emil Cioran, Petre Țuțea, Zaharia Stancu, or Ion Vinea. Each had his own place, known and respected by the entire clientele.

On the opposite side was the “Transylvanians’ table,” where Petre Țuțea dominated the discussions. There Cioran also made his entrance at Corso. The debates were heated. Țuțea, detached from the fascination with communism, passionately analyzed Spengler’s theories about the decline of the West, while Cioran intervened with ironic, often sharp observations. The world was “in hair,” as Vlaicu Bârna noted — a metaphor describing the intensity of the disputes.

More rarely appeared the group from the magazine and circle “Criterion,” including Mircea Eliade, Mircea Vulcănescu, Dan Botta, and Petru Comarnescu. They preferred the tables near the windows overlooking Calea Victoriei. After the conferences held at the Royal Foundation, the discussions continued at Corso until late at night. For them, the café was not just a space for socializing, but an extension of the intellectual dialogue begun in official halls.

In the novel “Return from Paradise,” Mircea Eliade immortalized the atmosphere at Corso, transforming it into the meeting place of Pavel Anicet’s friends. Although Eliade did not frequent the café daily and often preferred retreat for reading and writing, he could not ignore its symbolic importance in the life of his generation.

Viennese elegance and the ritual of the “șvarț”

The atmosphere at Corso was strongly influenced by the Viennese model. Patron Finkelstein brought to Bucharest Aloisus, a former “ober” on Ringstrasse, to instill in the venue a Western discipline and elegance. Waiters brought to the table magazines from all over Europe, and the client was treated with an almost ceremonial deference.

One of the symbols of the café was the “șvarț,” the star drink of the period. Prepared from equal quantities of coarsely ground coffee and chicory, strained and reheated, the drink resembled a black coffee without grounds. It was served in metal cups, alongside cube sugar and a glass of cold water. It was said that at Corso one drank the best “șvarț” in Bucharest.

Upstairs there was a games hall, with classic and American billiard tables, but also tables for chess and backgammon. Here, personalities such as Ion Vinea could be challenged to a chess match. Literary discussions intertwined with strategies on the board, and the apparent calm of certain senioral figures contrasted with the murmur in the downstairs hall.

Corsoleto and the splendor of Bucharest nights

Inspired by the Western chain Ciro’s, Finkelstein opened next to the café an annex venue, Corsoleto, with entrance from Franklin Street. The décor recalled a restaurant carriage of the Orient Express, with an exotic and sophisticated air. Here gathered the high society, attracted by the charm of the bar and the fashionable atmosphere.

Bucharest of the 1930s was famous for the beauty of its women, and the evenings at Corsoleto became true parades of elegance. Gentlemen, after a cocktail prepared by the bartender, got behind the wheel of luxury automobiles to parade along the boulevards. Romantic relationships, flirtations, and social ambitions were part of the nocturnal spectacle.

However, Corso was not only a space of frivolity. Here heavy words were also spoken against the Carolist regime. Opponents discussed openly, and rumors quickly reached the Royal Palace. Ernest Urdăreanu presented King Carol II with reports about the “mouth of the café,” and the Secret Police closely monitored hostile statements.

The end of an era

In 1939, the building that housed the café was demolished. Officially, the reason was related to the systematization of Palace Square. Unofficially, it was said that political reasons weighed heavily. Corso had become a focus of inconvenient opinions, a space of freedom of expression difficult to control.

With its disappearance, Bucharest lost not only an elegant venue, but a symbol of a generation. The war and the postwar transformations radically changed the cultural landscape. Literary cafés no longer had the same power of coagulation.

Today, Corso remains a mythical landmark of interwar Bucharest. In the memories of those who lived that period and in the pages of memoir literature, it continues to exist as a space of dialogue, of bold ideas, and of lost elegance. Its story is not only the history of a venue, but the chronicle of a world in which conversation was art, and coffee — a pretext for shaping the cultural destiny of a generation.

We also recommend: Fialkowsky Café, the decadent hangout of pre-war Bucharest where actors came to savor “wine mixed with witty words”