“Cold Drunkennesses” and the Forbidden Pleasures in Interwar Bucharest: Morphine, Cocaine and Ether Were the Stars of the Parties

By Andreea Bisinicu

- Articles

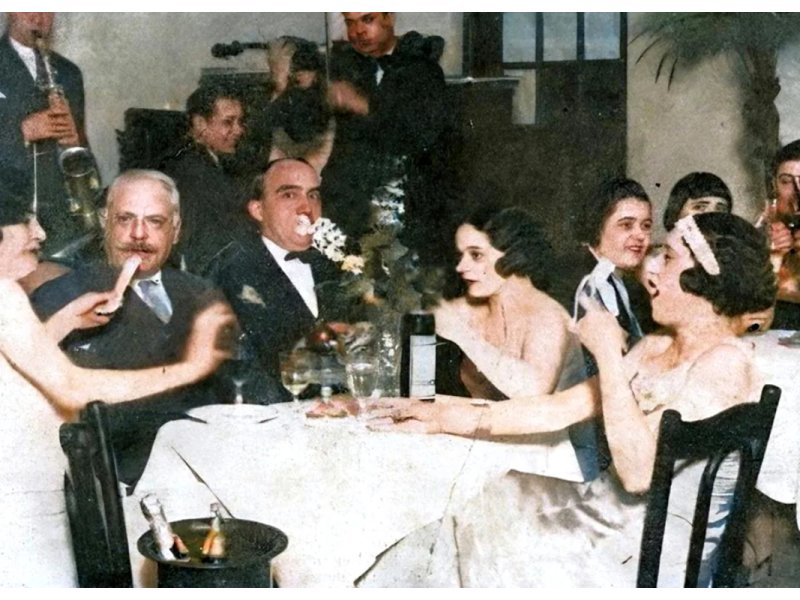

In the years between the two world wars, Bucharest was living through one of the most spectacular transformations in its history. The capital of Greater Romania had become a city of contrasts: elegant boulevards, cafés frequented by artists and politicians, influential cultural magazines, lavish balls and an intense nightlife. Little Paris had earned its reputation as a cosmopolitan city, open to the West, where fashion, literature and music intertwined with the ambitions of a society in full affirmation. Yet beyond the glitter of the salons and the optimism of an era that seemed to promise everything, a less visible reality was taking shape. In the shadow of parties and the enthusiasm of modernity, drugs were making their way into the lives of Bucharest’s inhabitants. Morphine, cocaine and ether – substances initially associated with medicine or scientific experiments – had become the “stars” of a world of excess. The press of the time spoke about “cold drunkennesses,” an expression that perfectly captured the insidious nature of addiction: a state of artificial euphoria, lacking the warmth of alcohol, yet capable of destroying lives.

A city of modernity and temptations

Interwar Bucharest was a city that pulsed with energy. The cafés on Calea Victoriei, luxurious restaurants and exclusive clubs attracted an elite eager for entertainment and self-assertion. Artists, writers, politicians and industrialists met in spaces where conversations about literature and politics alternated with music and dancing. Accelerated modernization brought with it a Western air, but also a freedom of morals that was not without risks.

In this atmosphere, temptations did not delay in appearing. Substances with psychotropic effects, many of them originating from the medical circuit, began to circulate more and more frequently. In a society marked by the traumas of the First World War and by the pressure of adapting to new political and economic realities, the desire for escape was strong. For some, drugs offered the illusion of a shortcut to relaxation, inspiration or oblivion.

Although consumption was not generalized, it had become sufficiently visible to attract the attention of the press and the authorities. Behind the elegant façade of the capital, a parallel world was taking shape, where extravagant parties were seasoned with fine powders and liquids with a sweet smell.

Morphine and the “cold drunkennesses” of addiction

Among all the substances circulating at that time, morphine held a special place. Discovered and widely used in the nineteenth century for its analgesic properties, morphine had been intensely used in hospitals, especially for treating the wounded from the war. Initially perceived as a progress of medicine, it gradually became a trap for those who discovered its sedative and euphoric effects.

In interwar Bucharest, morphine was no longer just a medicine, but also a means of escape from reality. Those who consumed it described a state of profound calm, of detachment from everyday worries. But this “calm” had a price. Addiction set in quickly, and the doses had to be increased in order to obtain the same effect.

Publications such as Ilustrațiunea Română dedicated entire pages to the phenomenon. A report from 1931 presented the disturbing testimony of a young woman trapped in the vicious circle of morphine. She described the “cold drunkennesses” as episodes of artificial floating, followed by painful crashes. Her will was undermined, her relationships shattered, and her identity gradually faded. From a lively woman, she had become a shadow, dependent on a substance that had taken over her existence.

The expression “cold drunkennesses” underlined the difference from alcohol: it was not about noisy exuberance, but about a numbing of the senses, an inner isolation. Precisely this apparent discreteness made morphine so dangerous.

Cocaine and ether, symbols of excess

If morphine was associated rather with a silent escape, cocaine had become the symbol of extravagant parties. With its stimulating effects, it promised energy, mental clarity and a state of exaltation. In the high circles of Bucharest, cocaine circulated at balls and social gatherings, being considered by some a sign of Western refinement.

The city’s elite was attracted to this substance that amplified the feeling of power and confidence. In a competitive environment, where image and social success mattered enormously, cocaine seemed to offer an illusory advantage. Yet, like morphine, it created addiction and brought serious consequences to physical and mental health.

At the same time, ether – a volatile liquid with a sweet smell – was spreading rapidly among all social classes. Initially used as an anesthetic, ether was inhaled for its narcotic effects. Unlike cocaine, the consumption of ether was not limited to elites. It could be encountered both in bohemian circles and in more modest environments.

Consumption often took place in plain sight, without much fear of consequences. The lack of clear legislation and efficient control facilitated access to these substances. In many cases, they were obtained through pharmacies or informal networks that took advantage of the growing demand.

The authorities in the face of a phenomenon difficult to control

As the problem became more visible, the authorities tried to intervene. Campaigns against drug trafficking and consumption aimed to reduce access to substances and to punish distributors. However, the efforts encountered numerous obstacles.

The sudden banning or drastic limitation of supply led, paradoxically, to market crises and to price increases. Instead of eliminating the phenomenon, these measures fueled the black market and made the substances even more desired. Addicts, desperate to obtain their dose, were willing to pay increasingly large sums, which sustained a vicious circle.

Moreover, the lack of an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms of addiction made intervention more difficult. Consumption was often regarded as a moral vice, not as a complex medical and social problem. Thus, those affected were stigmatized, and real support for recovery was limited.

Deaths caused by overdoses periodically shook the community, drawing attention to the seriousness of the situation. Each tragedy brought to the forefront the fragility of a society that, in its rush toward modernity and quick pleasures, had ignored the hidden risks.

Brilliance and decay in an era of contrasts

Interwar Bucharest remains in collective memory as a period of cultural effervescence and creative freedom. Literature, theater, music and the press experienced remarkable development. The city vibrated under the sign of hope and ambition.

Yet beneath this glittering surface, a dark reality was hidden. Drugs represented not only a fashion or an exotic curiosity, but a real problem, with profound impact on individual lives. Addiction transformed destinies, shattered families and left hard-to-erase marks.

Exploring this lesser-known chapter of history helps us understand the complexity of the interwar era. Modernity did not mean only progress and emancipation, but also confrontation with new temptations, for which society was not fully prepared.

The “cold drunkennesses” of morphine, the cocaine exaltation and the sweet vapors of ether are today echoes of a bygone era. But they speak about a universal human struggle: the desire for escape, the fragility in the face of temptation and the search for meaning in a world in continuous change. By understanding these stories from interwar Bucharest, we discover not only the shadows of the past, but also lessons that remain valid for the present.

We also recommend: The Stone Cross, forbidden love and the brothels of interwar Bucharest. The “sweet girls” read, spoke foreign languages and had good manners