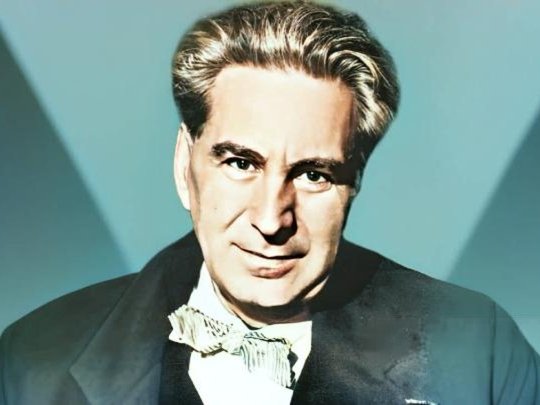

The eternal Don Juan of Romanian literature, whose wife supposedly found him mistresses. The story of George Călinescu

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

Few literary figures have led a life as full of contradictions as George Călinescu. A critic, literary historian, novelist, university professor, and academician, he was one of the brightest minds of Romanian culture — and yet, behind the image of a scholar devoted to books hid a man of passion, a Don Juan of the literary world, whose numerous love affairs even drew the attention of the communist secret police.

A genius of literature, a controversial spirit

Born on June 19, 1899, in Bucharest, under the name Gheorghe Vișan, his destiny was unusual from the very beginning. His biological mother, Maria Vișan, worked as a maid in the house of the Călinescu family. When the boy was only eight, he was adopted by Constantin and Maria Călinescu, childless railway employees. From that moment on, he became officially known as Gheorghe Călinescu — the name he would carry for the rest of his life.

Although he signed his works as “G. Călinescu,” following the intellectual fashion of the time, his name soon became synonymous with rigor and refinement in literary criticism. After earning a degree in Letters in 1923, he received a scholarship from the Romanian Academy to study in Rome, where he perfected his classical education. He was a self-taught genius with an insatiable intellectual curiosity — a man who lived for reading but also for the thrill of life.

In 1929, at the age of thirty, he married Alice Vera, the daughter of small Bucharest entrepreneurs. Their first meeting — full of charm and humor — would later be described in detail in his novel Cartea nunții (“The Book of the Wedding”). Together, the two led a modest life, far from the social glitter of literary circles. Although his in-laws could have provided financial comfort, the couple preferred to rent a small place, seeking peace rather than luxury.

In her diary, Alice Vera wrote candidly: “Our life was always modest. We lived withdrawn. We went once or twice a week to the cinema or to the theatre — my husband chose the shows. Visits? Rarely, one or two a year. I took care of the household; he took care of writing. He was very comfortable. Apart from his writing, he didn’t care about anything else.”

Călinescu was a man of extremes: disciplined yet passionate, reserved yet charming. While working on The History of Romanian Literature, he became almost inaccessible. His friend Lucian Nasta wrote in The Intimacy of the Lecture Halls: “He locks himself in for weeks when he has to write; he hides his address or gives fictitious ones, terrified by the thought of being interrupted.”

This obsessive need for isolation concealed a deeply emotional side. According to documents discovered after 1989, George Călinescu was monitored by the Securitate, the communist secret police, which noted in its reports details about his private life — details considered “inappropriate for socialist morality.”

The wife who found him mistresses

In 2014, one of his former students, Ionel Oprișan, published The Siege of the Fortress: The Securitate File of G. Călinescu, which revealed a series of informative notes collected between 1959 and 1961. Among the informants was one of his female admirers, who claimed that, at the age of 60, the professor had fallen in love with a woman named Liliana — thirty years his junior.

Even more surprising was the claim that his wife, Alice Vera, not only understood his passions but even helped him find mistresses. Behind this unconventional arrangement seemed to lie a refined form of tolerance and devotion — a tacit understanding that the genius of George Călinescu needed freedom to create.

Within Bucharest’s cultural circles, Călinescu’s charm was legendary. He was a man of elegance and wit, with sharp eyes and an irresistible sense of irony, capable of captivating anyone with his intelligence and presence. In an era dominated by rigid intellectuals, he radiated warmth and spontaneity.

As seductive as he was in his private life, Călinescu was equally rigorous in his work. He produced monumental studies such as The Life of Mihai Eminescu, The Works of Mihai Eminescu, and The Life of Ion Creangă, along with monographs dedicated to Nicolae Filimon and Grigore Alexandrescu. After 1945, he broadened his research to include world literature, publishing essays and critical studies of exceptional depth.

In 1953, his novel Bietul Ioanide (“Poor Ioanide”) appeared — a subtle satire of Romania’s intellectual society. From 1956, he maintained a weekly column titled The Optimist’s Chronicle in the cultural magazine Contemporanul. Although the communist regime viewed his independence of thought with suspicion, Călinescu’s intellectual authority was too great to suppress.

A scholar among books, music, and silence

The George Călinescu Memorial House, located today on the street that bears his name in Bucharest’s Sector 1, still preserves the atmosphere of the great scholar’s world. Built according to his own design, the house consists of two main rooms — the living room downstairs and the bedroom above. In the garden, beneath an old mulberry tree, stood a small fountain with jets of water among rose bushes — a creation of the writer, who loved both symmetry and quiet.

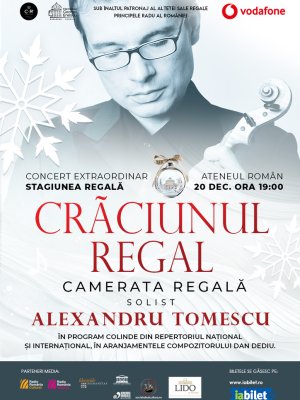

In the yard, a small annex with two tiny rooms served as his retreat. There, Călinescu would often withdraw to play the violin, fascinated by the way the walls resonated with sound. Music was a source of inspiration for him — he listened to Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart, and often attended concerts at the Romanian Athenaeum.

His “friends” in this little world were unusual: a tortoise named “Seneca” and a dog called “Fofeaza,” who appears under the name “Stolt” in his writings. At the far end of the courtyard stands his study — a small room with books stacked up to the ceiling. On his desk, a pen remains uncapped beside a few unfinished lines from The Optimist’s Chronicle, as if time itself had paused there.

Călinescu’s library is a veritable encyclopedia. The shelves hold rare editions of world literature — from Chinese hieroglyphic texts to medieval manuscripts, from Rilke and Valéry to young contemporary poets. Among them are autographed copies and rare editions in Italian, German, and French, alongside the works of Romanian poets. To him, books were living beings — extensions of the human spirit.

Despite the austere image sometimes associated with him, Călinescu had a refined playfulness and an infectious joy of life. In the preface to one of his monographs, he wrote: “To write about people means to live their lives.” Perhaps it was this empathy that made him both a great critic and a man vulnerable to the passions of existence.

His final years and the legacy of a titan

In November 1964, George Călinescu’s health declined rapidly. Hospitalized at the Otopeni Sanatorium with cirrhosis, he remained lucid until the very end. On the night of March 12, 1965, as Geo Bogza later wrote, “he left for the world of shadows under the cover of darkness, leaving behind a work fundamental to the culture of the Romanian people.”

The archives of Radio Romania still preserve the recording of his speech at the Romanian Academy on his 60th birthday — a moment of brilliance and irony, where he spoke about the destiny of Romanian culture with unparalleled intellectual vigor.

Călinescu remains a paradoxical figure: a moralist of passion, a scholar who loved life to excess. Though the image of the “eternal Don Juan” has often been exaggerated by gossip and secret police reports, the truth is deeper — he was a man who lived as intensely as he thought.

His house, now a museum, stands as more than a place of memory — it is a living testimony to the way genius and sensitivity can coexist. Behind the dozens of volumes, behind the monumental History of Romanian Literature and the luminous studies on Eminescu and Creangă, lies a man who loved and was loved in return.

Perhaps it is precisely this tension — between rigor and passion, solitude and desire — that made George Călinescu not only a great critic but also a myth of Romanian culture. The eternal Don Juan of our literature was not merely a conqueror of women but, above all, a conqueror of minds — those who, even today, rediscover in his pages the inexhaustible charm of life and art.

We also recommend: The passions of the nearsighted teenager of Bucharest: Mircea Eliade rowed on the Danube, climbed mountains, and played oina in the neighborhood