What taxes and levies Bucharest residents paid 100 years ago: houses, buses, sidewalks

By Andreea Bisinicu

- Articles

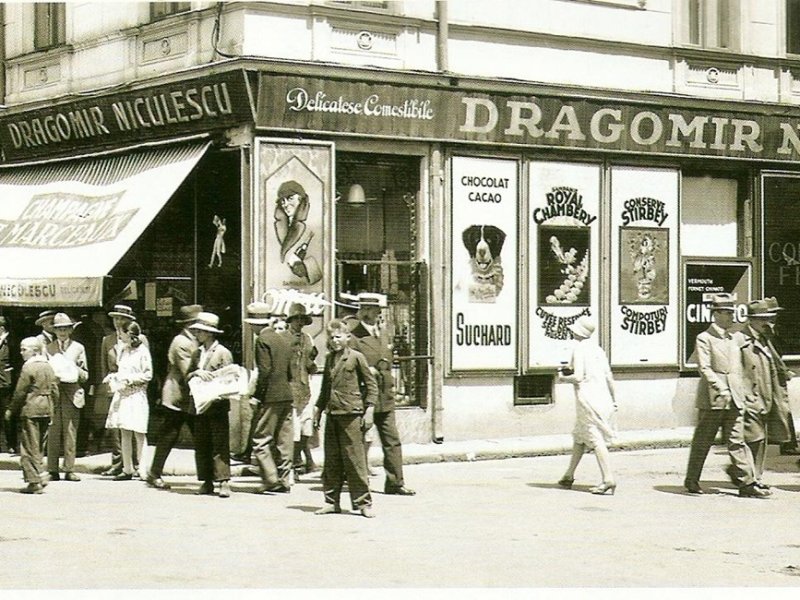

In 1930, Bucharest was a city poised between tradition and modernity, between the patriarchal rhythm of its outskirts and the ambition to become a fully European capital. Beyond elegant buildings, newly laid boulevards, and commercial effervescence, the city functioned on the basis of a well-established fiscal mechanism. Bucharest residents lived, in practice, with two parallel registers of payment: major taxes, established by law at national level, and communal taxes, collected directly by the local administration for services, authorizations, and the use of public space.

The “heavy” taxes: how incomes and properties were taxed

If the “heavy” taxes targeted incomes, properties, and businesses, communal taxes intervened in everyday life. You encountered them when you occupied the sidewalk with merchandise, when you requested a certificate, when you entered the city with a bus, or even when you organized your marriage. The fiscal image of interwar Bucharest is therefore a complex one, in which the state and the municipality divided responsibilities and revenues.

At the base of the fiscal system in 1930 were direct taxes structured by categories of income. The state attempted to identify and tax earnings “by source”: agricultural income, income from buildings, income from securities, income from commerce and industry, salaries, or liberal professions. On top of these sectoral taxes, a progressive tax on total income could also be applied, which meant that individuals with higher earnings ended up paying additionally depending on the total of their revenues.

For the urban environment, two types of taxes had special relevance. The first was the tax on the income of built properties. This functioned, in essence, as a tax on the net income obtained from the exploitation of buildings — whether it was rent or other forms of capitalizing real estate. Owners did not pay only for the simple possession of the house, but for the income generated by it.

The second major benchmark was the tax on the income of commercial and industrial enterprises. Merchants, craftsmen, and industrialists were taxed according to the net income achieved from their activity. The law established clear rates, and the fiscal administration monitored the declaration and verification of earnings. For a city like Bucharest, where commerce and small industry represented important economic engines, this tax was a consistent source of revenue for the state.

An essential aspect of the system was the possibility of applying additional quotas for the benefit of communes. This meant that, beyond the basic tax established at national level, the city could add a local quota, within the limits permitted by law. In practice, part of the money paid “to the state” returned to the municipal budget through this mechanism. It was a financial bridge between the central authority and the concrete needs of the Capital.

Communal taxes: the city as a permanent administrative mechanism

If direct taxes represented the skeleton of public financing, communal taxes were the nervous system of the city. They did not appear only once a year, but repeatedly, whenever the citizen interacted with the administration.

The municipality collected taxes for a wide range of operations: issuing authorizations, verifying and approving construction plans, cadastral operations, certificates, endorsements, or consulting systematization documentation. Any urban initiative — from the parceling of land to the erection of a building — involved an administrative cost.

Thus, Bucharest monetized its function as regulator. The city was not only a space of habitation, but also an organism that controlled urban development. Every stamp, every official document had a price. In this way, the local administration ensured constant revenues and, at the same time, exercised strict control over the way in which the city was transforming.

For the ordinary Bucharest resident, these taxes meant that almost any official démarche was conditioned by a payment. Whether it was a house plan, a modification of property, or obtaining a certificate, the relationship with city hall inevitably had a financial component.

The sidewalk as a fiscal resource: commerce and the occupation of public space

An eloquent example of how urban fiscality was conceived in 1930 is the tax for occupying the sidewalk. Merchants who displayed their goods in front of the shop had to pay a tax calculated per square meter. The sidewalk thus became a taxable surface when it was used for commercial purposes.

In a city in which shop windows often extended into the street, and crates of products, stands, or improvised tables occupied public space, this tax was extremely relevant. It was not felt only at the end of the year, but in the daily activity of the shopkeeper. Every square meter counted, and extending the shop beyond its walls meant an additional cost.

Beyond the financial aspect, the tax reflected a clear vision: public space belonged to the city and could be used for a fee. Interwar Bucharest understood the sidewalk not only as infrastructure, but also as an economic resource. Street commerce was allowed, but regulated and taxed.

Ceremonies and public services: how much a marriage cost

Municipal fiscality also touched important moments in private life. The officiation of marriages was subject to differentiated tariffs, structured by classes. There was an administrative hierarchy of the service, depending on conditions and probably on the status of the applicants.

It is interesting that the documents of the time also mention a special class intended for the needy population. This suggests that the administration attempted to combine the necessity of collecting taxes with a certain social sensitivity. Even in a system based on tariffs, there was the idea of differentiated access for those with limited resources.

Therefore, the marriage ceremony was not only a symbolic and legal act, but also a fiscal one. The city charged a fee for organizing and officially registering the event, and this fee varied according to the category into which the couple fell.

Mobility under control: taxes for buses and circulation

Transport represented another important area of fiscalization. Buses that entered and operated within the radius of the Capital were subject to circulation taxes and monthly payments. The issuance of special authorizations or booklets was required, and each vehicle that used urban infrastructure generated revenues for the municipality.

The principle was clear: not only possession mattered, but also the effective use of roads, stations, and termini. The city taxed circulation, parking, and operation within its limits. In a context in which motorized transport was becoming increasingly present, these taxes had both a fiscal role and a regulatory one.

Through these measures, the administration controlled vehicle flows and ensured an additional source of revenue. Urban mobility was not free of costs, and infrastructure was treated as a public good that had to be maintained and financed.

The road usage tax and the concession of urban space

Another interesting component of the fiscal system was the road usage tax, applied in cases where concessions were granted that affected the public domain. Crossings, the installation of lines, or other equipment that involved the use or modification of the street were subject to specific payments.

It was not a general tax applicable to all citizens, but an infrastructural tax. Whoever used or affected the public domain for private purposes paid for this privilege. The concept is extremely modern: the user bears the cost of the intervention upon common space.

Thus, the city not only collected money, but also imposed clear rules regarding the use of roads and infrastructure. Fiscality was, in this case, an instrument of balance between public interest and private interest.

A lesson about financing the city

Viewed as a whole, the Bucharest of 1930 was not only a city that collected annual taxes on income and property. It was a complex organism that built its budget from a multitude of smaller payments, integrated into everyday life. Direct taxes formed the base, but communal taxes represented the fine mechanism through which the administration ensured constant resources.

The sidewalk, authorizations, transport, ceremonies, concessions — all had a price. Space, time, and public services were evaluated and transformed into sources of revenue. In this way, the city financed its modernization, infrastructure, and administrative apparatus.

Perhaps the most important conclusion is that urban financing was not based only on major fiscal categories, but on a dense network of taxes linked to ordinary gestures. Interwar Bucharest managed its budget through a balance between general taxes and concrete tariffs attached to each interaction with the city. And this logic remains, in an adapted form, surprisingly current.

We also recommend: History with a taste of the past. “Caragiale’s Gambrinus Brewery, the fiercest rival of the famous Caru’ cu Bere