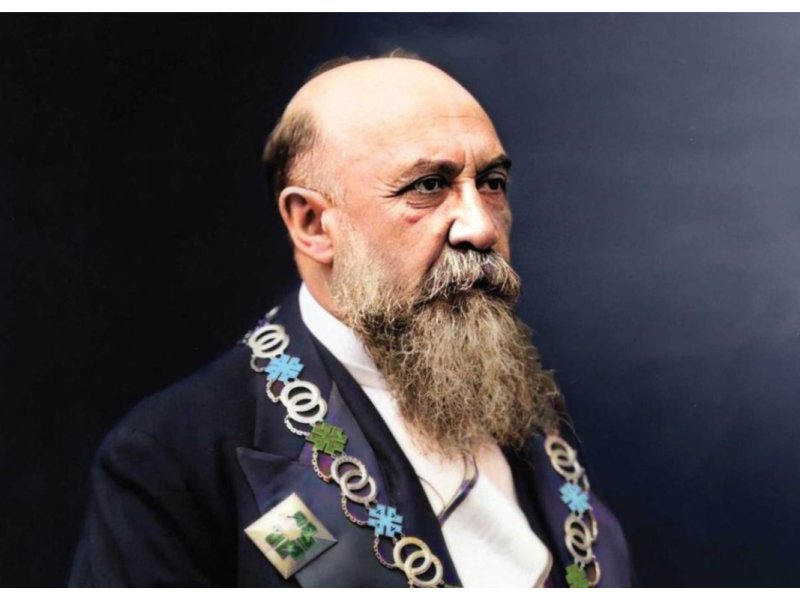

The brightest mind in Romania’s history, treacherously killed by the Legionaries 85 years ago. Nicolae Iorga – the man, the historian, the legend

By Andreea Bisinicu

- Articles

Nicolae Iorga was born on June 5, 1871, in Botoșani, into a cultivated and close-knit family: his father, lawyer Nicu Iorga, and his mother, Zulnia, both considered by many researchers to have Aromanian roots, provided him with an environment ideally suited for exceptional intellectual development. The fragile but inquisitive child quickly became one of the most impressive minds in Romanian culture.

The origins of a brilliant mind

From early adolescence, Iorga stood out through an insatiable thirst for knowledge, devouring countless books and displaying an extraordinary memory—an ability that would shape his entire career.

Throughout his life, Iorga was regarded as a complete scholar. His contemporaries, as well as modern specialists, described him as an encyclopedic spirit—historian, literary critic, playwright, poet, documentarian, encyclopedist, memoirist.

His seemingly endless work earned him the title of “the Romanian Voltaire,” a phrase used by George Călinescu, which perfectly captures the breadth of his activity and his intellectual power.

A scholar dedicated to culture and the state

Nicolae Iorga’s career reached the highest levels of scientific and academic recognition. He was a university professor, a member of the Romanian Academy, rector, founder of journals, creator of cultural institutions, and an organizer of Romania’s academic life. Through his extensive studies, lectures, and articles published both in Romania and abroad, Iorga became an uncontested authority in universal and Romanian history.

His strong personality and involvement in public life naturally led him into politics. He served as a member of parliament, minister, royal adviser, and, for a brief period, prime minister. Although his political activity was sometimes criticized, no one disputes that Iorga consistently upheld a moral and national vision of his responsibilities as a statesman and man of culture.

Confrontation with the Legionary Movement

In the 1930s, Romania was engulfed in political turmoil marked by the rise of the Legionary Movement. Loyal to democratic ideals and the authority of the state, Iorga openly criticized the organization.

His articles in the newspaper Neamul Românesc denounced the Legionary commercial initiatives and the dangers the movement posed to the country’s stability. He shut down Legionary-run canteens and mocked the idea of “green commerce,” warning about preparations “among dishes and pistols” for a potential uprising against the monarchy.

Tension escalated when Corneliu Zelea Codreanu sent Iorga a reprimanding letter, accusing him of dishonesty. Iorga responded by accusing Codreanu of insult and initiating legal action. Codreanu was sentenced to six months in prison, followed by an additional ten years of hard labor for attempting to overthrow the state order.

After his death on the night of November 29–30, 1938—strangled along with other Legionaries while being transported to Jilava, Legionary factions swore revenge. Iorga became the main target of death threats. They referred to him mockingly as “the sinister apparition with a beard and umbrella.”

The year 1940 and the unfolding tragedy

After September 4, 1940, once General Ion Antonescu came to power and formed the Legionary government, the environment became ideal for the radical actions of the Iron Guard. The atmosphere was tense, violent, and unstable. Iorga, already retired, had received numerous death threats and had even been advised by Antonescu to leave the country. Out of dignity and love for Romania, he refused.

On November 27, 1940, while at his villa in Sinaia, seven armed Legionaries broke into his home, claiming to be from the Legionary Police and that they had orders to take him in for questioning.

His wife, Ecaterina Iorga, later recounted that she was unable to resist them, while their daughter, Alina, returning from a walk with the family dog, saw her father surrounded by the armed men dressed in leather coats. Iorga was ill, weakened by a strong cold, but he was taken away without hesitation.

His final hours and the discovery of the body

On the morning of November 28, 1940, at 7:15 a.m., the lifeless body of Nicolae Iorga was found at the edge of the Strejnic forest in Prahova County. The report issued by Lieutenant Colonel Alexandru Ionescu briefly and coldly noted the discovery, the transport of the body to Bucharest, and the fact that the perpetrators remained unknown.

The reality was horrifying. The forensic report recorded nine gunshot wounds, two of them to the head, one entering directly through the brain. Although some witnesses claimed that the body had been mutilated, such details do not appear in any official report, likely out of respect for the scholar.

Researcher Eugen Stănescu confirmed the presence of nine cartridge cases at the crime scene and that Iorga had been shot near the roadside, with his fingers clasped in the sign of the cross—indicating he had likely been allowed to pray before being executed.

The identity of the assassins and the slow march of justice

Prosecutor George Octavian Toma, in a 2014 doctoral study, reconstructed the investigation and identified documents and testimonies suggesting the names of the possible killers. Among them were Traian Boeru, Teodor Dacu, Ion Tucanu, Ștefan Cojocaru, Ștefan Iacobuță, Gheorghe Cârciumaru, and Paul Cojocaru—all members of the Legionary Movement.

Justice was delayed for a long time, since the suspected perpetrators belonged to the ruling political faction. Only in 1941, after the Legionaries were removed from power, did Antonescu order the arrest of those responsible. Only two of them, Paul and Ștefan Cojocaru, were ever caught. The others vanished without a trace.

The press of the time remained suspiciously silent. At the University of Bucharest, not even a black mourning flag was raised. In contrast, universities abroad honored the memory of the Romanian scholar.

Reconstructing the crime and the legend of a violent death

Both Prosecutor Toma and historian Eugen Stănescu attempted to reconstruct Iorga’s last hours based on testimonies and documents. Although there is no official evidence of mutilation, persistent rumors claim that the Legionaries humiliated him before killing him.

What is certain is that, after the assassination, the same men reportedly celebrated at an inn near Predeal, showing off the weapon they said had been used to kill him.

Iorga’s death remains surrounded by mystery: missing reports, incomplete medical documentation, and a superficial initial investigation. Horia Sima, the Legionary leader in exile, later denied any involvement or prior knowledge of the plan.

A disappearance that marked Romania

The assassination of Nicolae Iorga represented one of the gravest blows to Romanian culture. It was not only a historian who died, but a monumental intellect, a man of dialogue, memory, and national education. His vast body of work remains a fundamental reference point for Romanian history. His violent death confirmed how fragile the life of a genius can be when political fanaticism takes hold.

His death was not just a political crime, but a deep wound in Romanian culture. Iorga remains the symbol of the dedicated scholar and the authentic patriot—a man who chose to remain in his country despite imminent danger.

A legacy that endures

Today, Nicolae Iorga is regarded as one of the most luminous figures in Romania’s intellectual history. His studies continue to be read, cited, and respected. The institutions he created, the books he authored, and his contributions to both universal and national history form the legacy of a man who lived entirely for culture.

Despite his tragic death, the legend of Nicolae Iorga lives on, and his memory is honored by all those who cherish truth, culture, and the authentic values of the Romanian nation.

We also recommend: The story of Sărindar Church, the chapel were Mihail Kogălniceanu, former Romanian prime-minister, got married