Bucharest’s hidden palaces: beyond the Palace of the Parliament

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

What do the city's forgotten buildings reveal about power, memory, and identity?

When you say “palace” in Bucharest, the mind jumps—almost reflexively—to the Palace of the Parliament. Monumental, immobile, overwhelming—it has become synonymous with the idea of “grandeur,” although it is more accurately a symbol of excess that was never ours, but belonged to a regime. Yet beyond this official, surveilled colossus, the city hides a parallel geography: invisible, semi-forgotten palaces, either private or crumbling, that don’t appear in guidebooks and are nowhere near the tourist’s checklist.

Architecture as a form of discourse

In Bucharest, power has always needed decor. Heavy façades, demonstrative columns, and inner courtyards meant to communicate, without words, who is in control. Whether it was the Phanariot aristocracy, the interwar bourgeoisie, or the communist nomenklatura, each left behind buildings that were never just “houses.”

They spoke. And they still do.

TakeGhica Tei Palace, for instance—with its sober neoclassical air and neglected garden, it seems to hold more stories within its walls than it shows. Bragadiru Palace, now used for private events, was envisioned as a refined public space for an emerging bourgeoisie that wanted to consume culture, not just status. And Suțu Palace, elegant and slightly theatrical, still plays the role of a silent spectator in a capital city that’s always in a hurry to forget.

The palace as a metaphor for forgetting

What makes these buildings fascinating is not just their architectural beauty, but the tension they carry in their very structure—between what they were and what they've become. Știrbei Palace, for instance, on Calea Victoriei, is a case study in itself: once an aristocratic residence, then nationalized, later turned into a luxury showroom, and finally closed. A kind of urban metamorphosis with no clear direction.

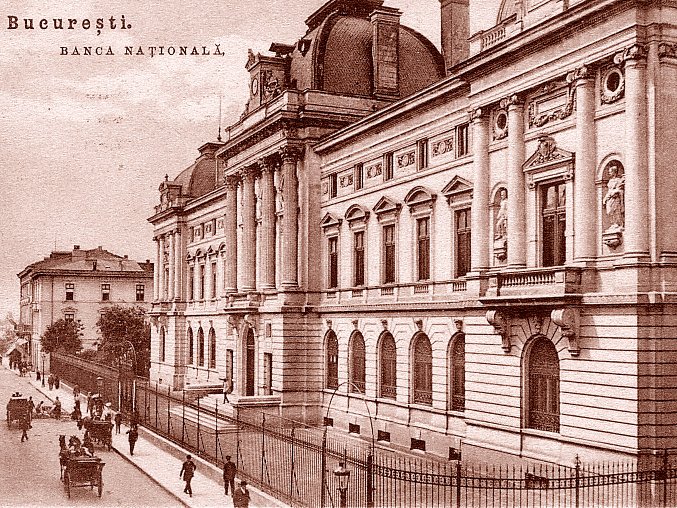

Or take Palatul Universul, once bustling with printing presses and newsrooms, now home to coworking spaces and creative industry offices—yet not without a certain friction between its interwar aura and present-day functionality. Chrissoveloni Palace, although impeccably restored by the National Bank of Romania, remains off-limits to the general public, functioning as a bank branch in a restrained and exclusive register. Both buildings are alive—but in a form reserved for the few, not for the city as a whole.

A different kind of heritage

To speak about Bucharest’s hidden palaces is to speak of a kind of heritage that isn’t featured in guides, but tells the truest story about the city. Not the tourist version—but the lived one. Not the monumental—but the intimate. These palaces aren’t visited on guided tours—they’re stumbled upon by people who choose to walk, to get lost on purpose, to see beyond shop windows and ads.

Other buildings have been reintegrated more visibly, like the Cantacuzino Palace (now the George Enescu National Museum)—a Beaux-Arts gem on Calea Victoriei, richly decorated and carefully restored to preserve its old-world atmosphere, yet mostly visited by music lovers and history enthusiasts. Or the Palace of the Chamber of Commerce, built between 1908–1911 in a classical style and only recently returned to public life after a long period of administrative use. It still impresses with its monumental façade and economic symbolism, but remains not fully reconnected to the city’s everyday life. Both buildings have returned to the urban fabric—but remain, ultimately, spaces for the interested few, not for the entire city.

Beyond aesthetics

These buildings are not just beautiful. They matter. They ask uncomfortable questions: What are we letting slip away? Who decides what gets preserved and what is left to decay? Why is a city’s aesthetic memory often seen as less valuable than its economic one?

In a city where every square meter is measured in profit potential, these palaces feel almost anachronistic. But perhaps that’s exactly why they deserve our attention: because they no longer serve an immediate purpose. They don’t generate revenue, but they can stir emotion. They don’t produce—but they preserve.

A different kind of map

Bucharest isn’t only what is seen. It’s also what is forgotten. The city’s hidden palaces don’t ask for applause. They only ask to be seen—with sharper eyes. They are not remnants, but quiet landmarks of a past that still breathes, even if in secret.

Beyond the Palace of the Parliament, the capital holds an entire collection of palaces that do not seek power—but understanding.