George Topîrceanu, the poetry, the fight on the front and the love story with Otilia Cazimir

By Andreea Bisinicu

- Articles

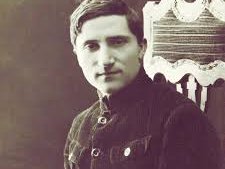

In 2025, 88 years have passed since the death of the illustrious poet George Topîrceanu, the better half of Otilia Cazimir, a good friend of the writer Mihail Sadoveanu and a brave Romanian sergeant who fought on the front of the First World War in 1916. Known especially for his fine irony and his poetic sensitivity, George Topîrceanu was not just a poet who wrote about the small joys and sorrows of everyday life.

The poet remembered after 88 years

Behind the image of the jovial artist hides a less known side: that of the soldier on the front line, the direct witness of the horrors of war. His participation in the military campaign in Bulgaria, during the First World War, changed not only his destiny, but also his writing.

His experience as a prisoner in the hands of the Bulgarians, following the dramatic defeat at Turtucaia, was recounted with remarkable sincerity and accuracy in his memorial volume Memories from the battles of Turtucaia. Pirin Planina.

Turtucaia, a locality that today belongs to Bulgaria, was part of the Romanian Cadrilater at the outbreak of the war. A bloody battle took place there between 1 and 6 September 1916 between Romanian troops and Bulgarian-German forces.

The ordeal of the Turtucaia defeat

The result was disastrous for the Romanian Army: over 6,000 soldiers and 160 officers lost their lives, while approximately 28,000 soldiers and 480 officers were captured. Among them was sergeant George Topîrceanu, who was already 30 years old and had a well-known literary activity. In his memories, Topîrceanu depicts with lucidity and compassion the sad image of Romanian soldiers, mostly untrained peasants, sent to the front without the necessary preparation or equipment.

He notes the difference between the heroic image of the Romanian soldier, as he had known it from the parades of the past, and the harsh reality of the battlefield.

“They were mostly peasants from the lowland counties of Muntenia, the most downtrodden of all,” he writes with a pain hard to hide.

His book is not only a literary testimony, but also a historical one, paying homage to these simple people who, although lacking experience, showed an heroism worthy of being recorded in the pages of history.

Topîrceanu acknowledges that the defeat at Turtucaia was a painful blow, but argues that it cannot define the character or courage of the Romanian people. “We had Turtucaia, but we also had Mărășești!”, he states, weighing failure and sacrifice against moments of glory of the Romanian army.

Captivity and the struggle for survival

After being captured by Bulgarian troops, Topîrceanu lived a year and a half of ordeal. He witnessed and suffered hunger, cold, disease and exhausting labor.

Under these conditions, however, the poet continued to observe, with the eye of a chronicler, the profound nuances of the human experience in war.

In a disturbing episode, he describes how exhausted and disoriented Romanian soldiers loot abandoned carts in search of alcohol, in an almost apocalyptic landscape.

One of the strongest images is that of a wounded artilleryman who, in the madness of pain, sprinkles sugar with his own blood and ritually utters the words:

“Take, eat, this is my blood which is shed for you…”

But despite the tragedy, his captivity was not without moments of humanity and even humor. In his volume, Topîrceanu recounts how, though unqualified, he became for a while “responsible” for a locomotive.

In another situation, he acted as interpreter for a Greek who claimed to be a doctor. With intelligence and improvisation, they managed to achieve successes in caring for other prisoners.

A reporter of the front and an observer of humanity

Philologist Mircea Morariu notes how Topîrceanu transformed suffering into a work valuable not only stylistically but also journalistically.

The poet becomes a true front-line reporter who describes not only the horrors of the confrontation, but also the subtleties of human interactions between prisoners and their captors.

“Not all Bulgarians were cruel,” he confesses, adding that war is not a clear line between good and evil, but a succession of chaotic events and ephemeral relationships, born and lost in the great confusion of conflict.

Topîrceanu makes a radiography of the condition of Romanian prisoners, highlighting the total degradation to which they were subjected. The lack of hygiene, food and medical care turned these men into shadows of themselves:

“Our unfortunate peasants had nothing human left in them… they looked like corpses that rose with earth on their heads and came out into the daylight.”

He was eventually hospitalized in Sofia after becoming seriously ill. Conditions were so precarious that survival seemed more a coincidence than a certainty. Prisoners were left to their fate, without laws to protect them, without support, without hope.

Return to Romania and the mark of war

Topîrceanu was released only in December 1917, most likely through the intervention of Constantin Stere, an influential political figure close to Germany. His return home was a surprise for many acquaintances who believed him dead, due to the lack of any news from the camp.

The experiences lived by Topîrceanu during the war did not embitter him, but deepened him humanly. He saw in simple soldiers not just victims of a global conflict, but symbols of a people thirsty for dignity and peace.

Although he did not write traditional war poetry, his observations and accounts stand as testimony to a profound understanding of the human condition in times of crisis.

Returned from the Bulgarian inferno, George Topîrceanu continued to write, publish and offer humor and reflection to his public. Yet the mark left by the war remained deep.

The poet would die on May 7, 1937, struck down by liver cancer, at only 51 years old. A relatively short but intense life, lived with lucidity and transposed with talent into literature.

Today, when his name is associated mostly with Cheerful and sad ballads, we should remember that there was another Topîrceanu – not just the poet, but also the soldier, the prisoner, the witness of a suffering nation.

The tragic and passionate love between Topîrceanu and Otilia Cazimir

The love story between George Topîrceanu and Otilia Cazimir has written history in the hearts of the romantics of Romanian literature, their romance being sprinkled with tragedy, passion and broken promises. They met in the house of the great Mihail Sadoveanu, and from then on, nothing was the same.

It is no surprise that in the Romanian literary world, love ties are often just as captivating as the works of the authors themselves.

One of these unforgettable stories is that between Otilia Cazimir and George Topîrceanu, two of the most important poets and writers of the 20th century. Their relationship was complex and profound, marked by a powerful emotional and artistic bond, but also by the tragedy that ultimately separated them far too early.

Otilia Cazimir and George Topîrceanu met for the first time in the home of novelist Mihail Sadoveanu, in interwar Romania. She was 17, he was 25. It was love at first sight, as they bonded during literary discussions, talking about art, music, literature and poetry. The two lovers collaborated on several cultural projects, writing together for the literary magazine Gândirea.

Both were known for their fine humor, intelligence, sarcasm and exceptional poetic abilities, and their collaboration contributed significantly to creating literary masterpieces of those times.

Letters, promises and a heartbreaking end

Their passionate love story has been preserved for posterity in the hundreds of letters they sent each other daily to express their burning feelings. They loved each other like in the movies and swore eternal love, but the cold claws of death spare no one.

In May 1937, George Topîrceanu passed away at just 51 years old, due to a terrible illness, and the shock of losing her beloved marked Otilia Cazimir forever.

Devastated by grief, the beloved of the late poet described, as best she could, through a letter, the terrible feelings that overwhelmed her the first time she visited the cold grave of her soulmate.

“May 16, 1937. Sunday evening. Today I went to the cemetery, for the first time since then. I also took carnations from you (I hadn’t yet finished the money for flowers). His grave, do you understand these absurd words?

His grave! But I didn’t feel him there, underneath. He is somewhere else. I will look for him and I will find him. I miss him too much for him not to be anywhere.

I am tired. More and more tired. I feel like sitting down by the roadside and dying. But… I have no time. I have so much to do!

For two days I worked, at Mr. Sadoveanu’s vineyard, to put a bit of order in his manuscripts. His notebooks, his notes, piled in a sack! I took them out, smoothed them, arranged them.

Philosophy, psychology, physics, studies about style, verses, the play Papură-Vodă, Microcosm. So deeply did it move me, so terribly did the immense wealth of priceless material lost scare me, so exhausted did the effort leave me, that I came home ill, with my body caught in bad pains, with clenched jaws.”

We also recommend: The muse who killed her gods: The woman who buried poets Dimitrie Anghel and Șt. O. Iosif