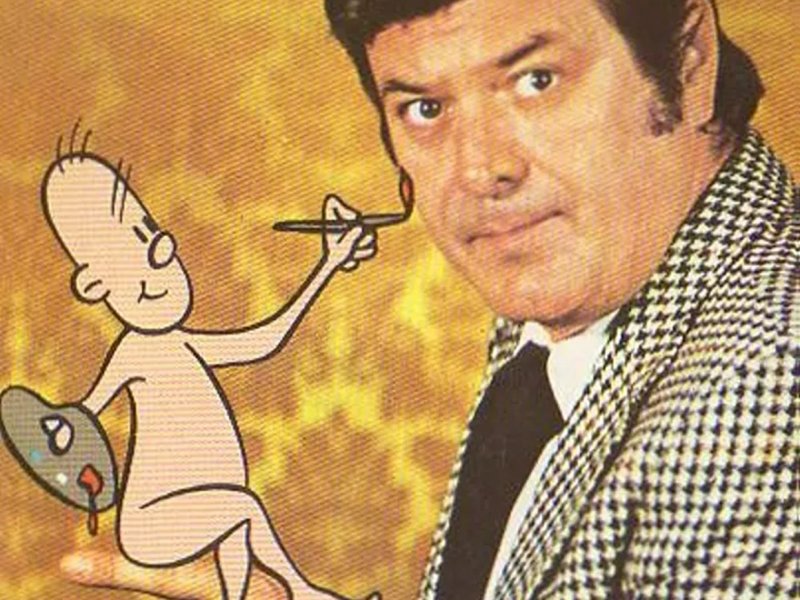

The history of the great Ion Popescu Gopo, the father of Romanian animated films

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

The name of Ion Popescu Gopo is today inseparably linked to the prestigious film festival that bears his name and takes place annually in Romania. The choice of this symbol was not accidental. The association of the great artist with the most important film festival in the country also made possible the transformation of the emblematic Gopo-little-man into a “pseudo-Oscar”-type statuette, which has become a visual landmark for Romanian cinematography.

The beginnings of a visionary artist

Ion Popescu Gopo was born on May 1, 1923, in Bucharest, in an artistic environment that would deeply influence his destiny. His debut in press caricature came early, in 1939, and his passion for drawing led him to the Academy of Arts in the capital.

An essential stage in his training was the specialization in animation followed in Moscow, where he came into contact with modern techniques and concepts for that period. This experience would form the basis of his unique style, which would find expression starting in 1949, the moment considered the official beginning of his career in animation.

The first animated short film created by Gopo was Punguța cu doi bani, inspired by the well-known story written by Ion Creangă. The film represented a demonstration of how the young artist managed to combine the literary text with his own vision, laying the foundation for a working philosophy that would set him radically apart from the dominant Disney style.

The birth of the Gopo-little-man and the anti-Disney philosophy

The famous Gopo-little-man, the symbolic character of his creation, appeared as a consciously assumed reply to the rich, ornamented aesthetics of Western animation. “He was not built as a character for children,” the artist explained, emphasizing that he wanted to create a “simple style, without the usual garnishes,” a sort of anti-Disney reaction. However, he acknowledged that spectators inevitably associated the character with childhood, because it was a pure figure, naive, sincere through its simplicity.

Despite this positioning, Gopo did not deny his fascination for Snow White, the film that deeply marked him and showed him the enormous potential of animation. For him, animation was itself a modern form of fairy tale, a medium that stages just characters, greatly tested, yet always victorious. In addition, he attributed to it a deeper dimension: the animated hero gained a unique quality – indestructibility – reflecting the human aspiration toward immortality.

When he was not drawing, Gopo diversified his passions. According to the interview published in Cutezătorii in 1982, the artist wrote music for films, sculpted, played with his Pekingese dog, Moacă, and often repaired various things around the house. A technical and creative nature at the same time, Gopo harmoniously combined art and pragmatism.

International recognition and defining creations

The moment that would definitively mark Ion Popescu Gopo’s career came in 1957, when he won the Palme d'Or Grand Prize at Cannes for the short film Scurtă istorie (A Brief History). This historic achievement demonstrated not only his exceptional talent, but also that Romanian animation could compete at the highest international level.

After this success, Gopo increasingly focused on films for children, but also on complex productions in which he was, in turn, director, screenwriter, or actor. Among the important titles are S-a furat o bombă, De-aș fi… Harap Alb, De trei ori București, Comedie fantastică, Povestea dragostei, Maria Mirabela, Galax, Rămășagul, or Maria Mirabela în Tranzistoria. These films helped define a recognizable cinematic universe, in which humor, fantasy, and moral messages blend in an unmistakable manner.

However, the world of Romanian film was not without controversy. One of the most sensitive stories is linked to the feature film Robinson Crusoe, produced by Animafilm and directed by Victor Antonescu. The film was ready to be released even during the communist era, but reached theaters only on June 1, 1990, after the fall of the regime.

The “Robinson Crusoe” case and the controversy that left deep marks

Although completed and initially approved for screening, Robinson Crusoe never managed to be seen by the Romanian public at the right time. The story is worthy of a film in itself. The feature film was presented in March 1973 to the president of the Council of Culture and Socialist Education, Dumitru Popescu, known as “God.” He had no objections and the film was sent back to the studio, with an established premiere date: May 26, 1973.

Things took an unexpected turn. Shortly after, Gopo, who was then in Geneva working for UNESCO, learned about the production and requested to watch it. After congratulating the director, he left without suggesting any problem. However, later that afternoon, the Council of Culture requested a new screening, and the next day the film was officially banned.

Director Victor Antonescu later revealed that the main reason for blocking the film would have been the intervention of Ion Popescu Gopo himself. The artist supposedly could not accept the idea that someone else in Romania might make the first animated feature film, considering that this honor rightly belonged to him. Moreover, a few years later, he tried to compensate for the situation through his own projects, but the precedent had already been set.

There were also two official justifications for the ban, as absurd as they were politically motivated:

– the film could offend African countries by presenting them as cannibals;

– if whites had been black and vice versa, the film would have been acceptable.

Thus, one of the projects that could have rewritten the history of Romanian animation was abandoned at a decisive moment, in a period when political decisions often exceeded artistic logic.

Gopo’s legacy and his impact on Romanian culture

Even though the Robinson Crusoe episode left behind uncomfortable questions, Ion Popescu Gopo’s legacy remains colossal. He created a visual language of his own, proved that Romania could excel in animation, and inspired entire generations of artists, directors, and animators. His little-man is today a timeless symbol, a representation of playfulness, curiosity, and human sincerity.

The Gopo Festival continues to honor his name, and the statuette inspired by his character keeps alive the essence of a unique personality in Romanian cinematography. Ion Popescu Gopo remains, without doubt, the father of Romanian animated films and one of the most visionary artists our culture has known.

We also recommend: Tudor Arghezi and the 11 professions. What the great poet worked at before becoming a legend of Romanian literature