“Timpul”, the classics and the literary legacy. Where the editorial office of the most famous Bucharest newspaper of the 19th century was located

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

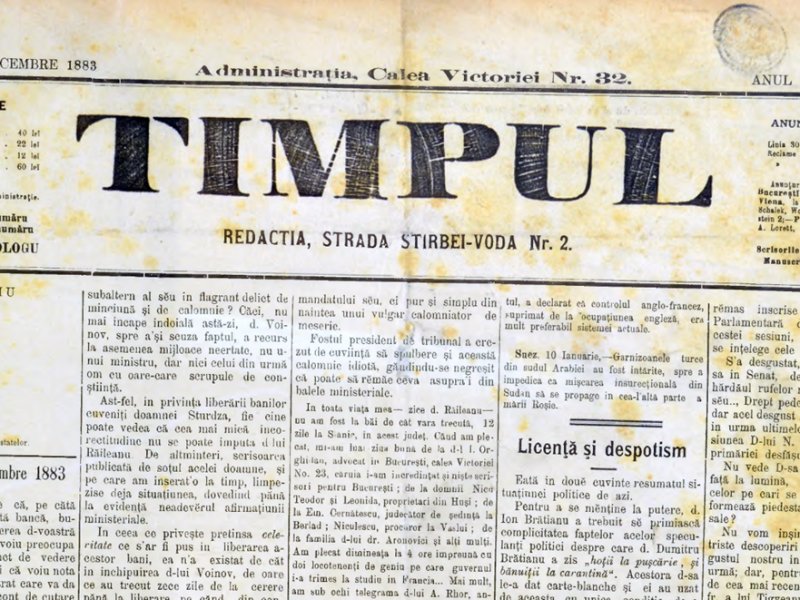

A total of 149 years ago, on March 15, 1876, the Conservative Party newspaper Timpul (“The Time”) appeared in Bucharest, initially published four times a week between 15 March and 16 May 1876, then daily between 17 May 1876 and 17 March 1884, later from 13 November 1889 to 14 December 1900, and finally in its last series from 2 March 1923 to 7 July 1924. Among its most renowned editors were Mihai Eminescu, Ioan Slavici and I. L. Caragiale.

The birth of a defining newspaper for Romanian culture

The new daily sought, through its editorial policy, to ensure “an impartial and, as far as possible, complete presentation of the various ideas that stir public opinion in Romania.” The newspaper was financed through party member contributions, although part of the Conservatives – including P. P. Carp and Th. Rosetti – advocated for its dissolution.

“Timpul”, described as a “political, commercial, industrial and literary newspaper,” appointed Gr. H. Grandea as editor-in-chief starting 21 November 1876, after he had already earned a strong journalistic reputation through his work at Curierul Bucureștilor.

In January 1877, the editorial office was taken over by Titu Maiorescu, while Ioan Slavici became responsible for the literary section and foreign affairs. In April of the same year, the Junimea mentor withdrew from the newspaper’s leadership, leaving management in the hands of Slavici, Gr. H. Grandea and G. I. Pompilian.

Financial challenges and Slavici’s appeal for support

The newspaper went through significant financial difficulties, a reality revealed in Slavici’s letter to Iacob Negruzzi, written on 5 August 1877:

“You will believe me when I say that I have not written to you until now because it was impossible for me to find a few moments of inner peace. For about fourteen days almost no one has come to the editorial office of Timpul, so only two people, myself and Pompilian, have had to fill its columns. Grandea is working at Războiul because no one pays him anymore at Timpul, and the man must make a living.

I myself haven’t been paid for three months. […] I live only God knows how; corrections, foreign reviews, notes from newspapers, miscellanea — this is my daily nourishment” (quoted in E. Torouțiu, Studies and literary documents, vol. II, Iași, Junimea Publishing House, 1931, p. 280).

Seeing himself without the resources needed to continue, Slavici called on Eminescu to come from Iași, where he had been editing Curierul de Iași. At the beginning of October 1877, a telegram from Maiorescu informed the poet of the offer to join the conservative newspaper in Bucharest:

“You are offered collaboration at Timpul together with Zizin Cantacuzino and Slavici, with 250 francs per month. Rosetti and I ask you to accept and to leave immediately for Bucharest.” (Quoted in D. Vatamaniuc, Eminescu’s Journalism, 1877–1883, 1888–1889, Minerva Publishing House, Bucharest, 1996, p. 13).

Eminescu’s entry into the editorial office marked a turning point in his journalistic career. For six years he carried out his most intense journalistic work, serving successively as editor, editor-in-chief and political columnist.

Eminescu, Caragiale and Slavici — a legendary team

For six years, “the Morning Star” of Romanian poetry published unsigned political articles, domestic and foreign chronicles, notes, reviews and studies, standing out through his sharp wit and rigorous thinking. Once he joined the editorial team, the quality and diversity of the newspaper’s content increased significantly: the literary section grew stronger, and more articles on sociology, social history and political analysis were included.

At Eminescu’s invitation, Caragiale joined the team in the spring of 1878, remaining editor until the spring of 1881.

Slavici contributed prose, reviews and notes; Caragiale wrote major editorials such as National Liberals (29 March 1878), Liberals and Conservatives (8 April 1878), What is the Center? (14 November 1878), as well as parliamentary reports, domestic and foreign news, information notes and theatre chronicles. Eminescu remained responsible for the domestic and foreign political pages.

In his writing, Eminescu often went beyond conservative doctrine, freely expressing his personal convictions, even when they conflicted with those of the party financiers. Thanks to the brilliance of his style, Timpul articles were frequently reproduced in other papers of the era. Many times Eminescu entered into disputes with the editors of Românul, creating the famous press duels that fascinated contemporaries.

Although the names of the three now classical writers did not appear on the newspaper’s front page, they bore full responsibility for all published material.

Friendship, discipline, and the craft of writing

From the memoirs of Slavici and Caragiale we understand the spirit that reigned in the newsroom. Referring to the friendship between Eminescu and Caragiale, Slavici wrote:

“Two men, very different in many respects, who sought each other and rejoiced whenever they could spend an hour or two together.

It was a pleasure not only for themselves but also for anyone who saw them together.” (Ioan Slavici, Memories: Eminescu, Creangă, Caragiale, Coșbuc, Maiorescu, Minerva Publishing House, Bucharest, 1983, p. 157). Regarding their writing discipline — a subject extremely relevant today in an era dominated by digital culture, Slavici noted:

“They both insisted on reading their texts together before sending the manuscript to print. It was a very wise practice, but they did not limit themselves to reading; they began discussing the language, then the ideas, and lost themselves in debates while the typesetter demanded more manuscript. But both believed that whatever was to be read by many had to be written with great care, and they paid no attention to the typesetter’s insistence.”

The literary prestige of “Timpul”

Literature held a prominent place in the newspaper: the sections Timpul’s Feuilleton and The Literary Section included translations of world literature (Schiller, Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Verne, Alexandre Dumas, Cervantes, Gogol, Pushkin, Jules Mary, Leon Allard, etc.) as well as works by Romanian writers.

Al. Macedonski published Ode Dedicated to the Romanian Army (no. 178/1877) and Ballad (no. 214/1877). Slavici contributed his novellas A Lost Life (no. 21/1877) and Budulea Taichii (no. 148/1880). From Convorbiri literare the paper reproduced poems by Eminescu, prose by Iacob Negruzzi (Fallen Leaves, no. 33/1877), Ion Creangă (The Story of Harap-Alb, no. 181/1877; Popa Duhu, no. 249/1881), the letters exchanged by Ion Ghica and Vasile Alecsandri (no. 95/1880), as well as major critical essays such as The Drunkenness of Words in Revista Contimporană (no. 200/1878) and Romanian Literature and the Foreign World (no. 18/1882).

Literary reviews by Titu Maiorescu, Eminescu, Slavici, Caragiale, Al. Vlahuță and N. Iorga appeared regularly, while D. Rocco and N. Popa contributed theatre and art chronicles.

The Dacia Palace on Calea Victoriei — the iconic home of the newspaper “Timpul”

The editorial office of Timpul operated on the first floor of the Dacia Palace (Palatul Dacia), an elegant building located on Calea Victoriei, one of Bucharest’s most prestigious boulevards. Constructed in the second half of the 19th century, the palace embodied the architectural refinement of the era, combining neoclassical influences with modern urban elegance.

Situated in the vibrant heart of the capital, Dacia Palace became a hub of cultural and political dialogue. Writers, journalists, politicians and intellectuals crossed its threshold daily, turning the editorial office of Timpul into a true laboratory of Romanian modern thought. The building’s central position facilitated rapid access to institutions, theatres, cafés and salons where ideas circulated freely and where public debates helped shape Romania’s cultural and political landscape.

Inside the palace, the first-floor offices of the newspaper hosted the long nights of writing, revision and discussion between Eminescu, Caragiale and Slavici. These rooms witnessed heated debates, the polishing of major editorials, and the birth of many influential articles that would shape public opinion in Romania. Today, Palatul Dacia remains an important architectural landmark, carrying the memory of the bustling, effervescent newsroom that once defined Romanian journalism.

We also recommend: The Universul Palace, the ambitious project of journalist Luigi Cazzavillan and the history of Romania’s first high-circulation newspaper