The History of the Hagi Moscu House, the First Building to Host Bucharest City Hall in the 19th Century

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

At the beginning of King Carol I’s reign, Bucharest entered a period of extensive modernization aimed at bringing the city closer to the image of major European capitals. Streets, public buildings, and state institutions were being rebuilt or newly constructed according to Western models, while the local administration sought to give the city an appearance worthy of a royal capital.

Bucharest Begins Its Modernization

At that time, every important institution—from ministries to local administrations—wanted an imposing building that would reflect its power and prestige. Bucharest City Hall was no exception.

Although urban plans envisioned a grand palace dedicated to city administration, this dream was never realized. Instead, the history of the first building that housed the institution—the Hagi Moscu House—remains fascinating, marked by ambition, architecture, demolitions, and unfulfilled promises.

Hagi Moscu House – An Imposing Boyar Residence

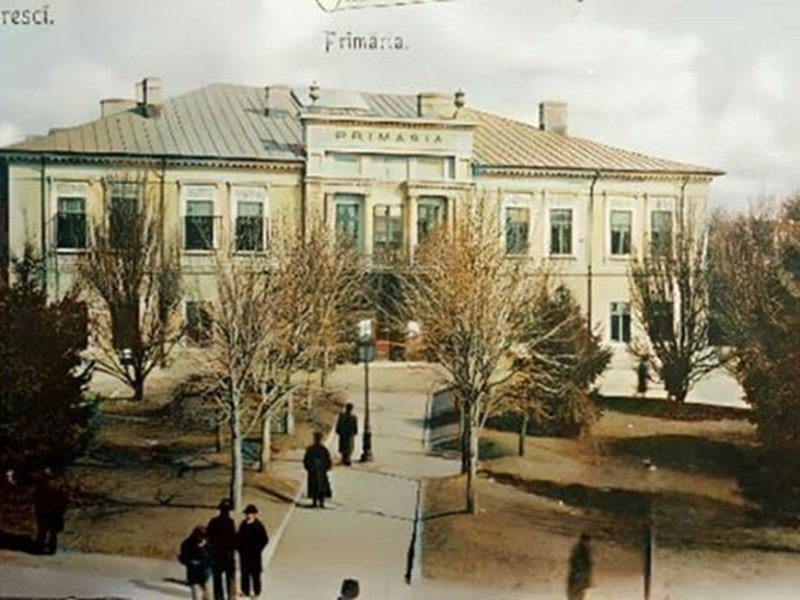

The story begins in 1810, when the wealthy treasurer Hagi Moscu built an impressive boyar residence on a generous plot in the very center of Bucharest. His estate extended over the area that today houses the National Theatre of Bucharest and the surrounding green spaces.

The house, designed in a neoclassical style, was one of the most beautiful in the city, featuring elegant columns, a spacious courtyard, and typical outbuildings of early 19th-century boyar residences.

After Hagi Moscu’s death, the house was inherited by his descendants, who, in 1882, sold it to the Bucharest City Hall to become the institution’s official headquarters. For several decades, the city administration operated from this historic building.

The Need for a Modern Headquarters

By the early 20th century, with the city’s rapid growth and the expansion of local government duties, the building had become insufficient. Offices, archives, and staff spaces were overcrowded, and conditions no longer met the needs of a modern capital.

In this context, the mayor at the time, Dimitrie Dobrescu (1911–1912), decided to demolish the old Hagi Moscu House to make way for a new, larger building. The demolition took place exactly a century after the house’s construction, and an architectural competition was organized for the new City Hall Palace.

First Architectural Competitions

The winner of the first competition organized by authorities was architect Petre Antonescu, one of the most important Romanian architects of the era. His plan proposed an imposing building with a tall central tower flanked by two smaller turrets, a structure that would have completely transformed the appearance of central Bucharest. The project echoed the monumentality of the Ministry of Public Works Palace, also designed by Petre Antonescu.

Other notable architects submitted designs as well. The famous Ion Mincu proposed a palace in the Neo-Romanian style with French influences, harmonizing local tradition with Western refinement. Gheorghe Sterian offered a design inspired by Viennese architecture, elegant and sophisticated, while the Italian Giulio Magni imagined a sober, balanced construction dominated by a monumental central tower.

Unfortunately, the outbreak of the First World War halted all efforts. Bucharest remained without a City Hall palace, and the vacant plot intended for construction became known as the “Maidanul Primăriei.” Over time, a few barracks and small shops appeared on the site, changing the purpose of the area.

Interwar Attempts

After the war, authorities revived the idea of building a Municipal Palace. A new competition was organized, with stricter rules and an important architectural requirement: the central tower of the building had to align with Edgar Quinet Street.

The winning project, designed by architects Toma T. Socolescu and D. Petru-Gopeș, was controversial. Although selected, the plan did not comply with the committee’s requirement—the main tower faced Bulevardul Carol I, in the opposite direction.

Other projects attracted attention for their innovation, such as the design submitted by architects D. Walter and Harrz Schoenberg, who proposed a building extending to Bulevardul Carol I and connecting to Colțea Hospital through a monumental gate inspired by Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate. Beneath this gate, pedestrians and vehicles would circulate—a visionary concept for Bucharest at the time.

Even this second attempt did not materialize. Lack of funds, political instability, and shifting urban planning priorities once again led to the project’s abandonment.

Final Projects and Permanent Abandonment

With the ascension of King Carol II, the architectural direction of the country changed. The monarch favored massive, sober buildings with simple, imposing lines, inspired by the fascist architecture of Mussolini’s Italy. In 1935, a third competition was organized for the Bucharest City Hall Palace.

Once again, Petre Antonescu won and adapted his vision to the new requirements: a sober building, stripped of decoration, consisting of three distinct volumes with three vehicular entrances. The palace had an L-shaped plan, with the northern wing parallel to Batiștei Street, and the main wing extending over the area where today the National Theatre of Bucharest stands. The facade resembled the current Government Palace, and a tall Art Deco-style clock tower rose on the southern side.

This building was intended to finally host the city administration. However, after King Carol II’s abdication and Romania’s entry into the Second World War, the project was abandoned permanently. After 1945, during reconstruction, the communist authorities renounced the idea of building a monumental palace for City Hall, relocating the institution to the building on Bulevardul Elisabeta, where it still operates today.

The Legacy of Hagi Moscu House

The land where Hagi Moscu’s house once stood, known as “Maidanul Primăriei,” was later used for the construction of symbols of the new regime: the National Theatre of Bucharest and the Intercontinental Hotel, two of the most iconic buildings of the communist period. Few today remember that the elegant Hagi Moscu House once occupied this site—a building that witnessed the beginnings of modern Bucharest administration.

The history of Hagi Moscu House reflects the transition from early 19th-century boyar Bucharest to the modern capital of the early 20th century and symbolizes the unfulfilled dream of a palace worthy of Bucharest City Hall. On the site where a boyar residence once stood, then a public institution, and later a cultural landmark, an important chapter of the city’s history is concentrated.

The Hagi Moscu House no longer exists, but its story remains a key chapter in the history of a Bucharest that always dreamed of modernity while gradually losing parts of its past.

We also recommend: The history of Nifon Palace, the most beautiful building on Calea Victoriei, from the inn of the furrier Dedu to the present day