Operation Autonomous. How writer Mihail Fărcășanu escaped from communist Romania aboard a bomber

By Bucharest Team

- Articles

The history of postwar Romania abounds in shattered destinies, forced exiles, and extreme acts of courage. Among them stands out the story of Mihail Fărcășanu, a liberal intellectual, talented writer, and anti-communist activist, whose spectacular escape from Romania in the autumn of 1946 became one of the most dramatic pages of Romanian political resistance. The so-called “Operation Autonomous” was not merely a flight from a repressive regime, but an act of moral survival in an era dominated by Stalinist terror.

The formation of a European intellectual

Mihail Fărcășanu, also known by the literary name Mihail Villara, belonged to a generation shaped in the spirit of Western culture. He pursued studies in law successively in Bucharest, London, and Berlin, acquiring a solid juridical and political education. In the capital of Hitler’s Germany, in 1938, he defended his doctoral thesis on the concept of social monarchy, a work later published both in Germany, in Würzburg, and in Romania, in 1940.

In that same decisive year he married Pia (Olimpia) Pillat, daughter of the poet Ion Pillat and sister of Dinu Pillat, thus entering a prestigious intellectual and political circle close to the Brătianu family. This alliance was to consolidate his position within the National Liberal Party, but also to turn him into a visible target for the future communist regime.

Political rise and the struggle for democracy

After returning to the country, Mihail Fărcășanu became deeply involved in political life. He became president of the National Liberal Youth and editor-in-chief of the newspapers Românul and later Viitorul, publications that functioned as genuine tribunes of Romanian liberalism. After 23 August 1944, when Romania switched sides in the war, he consistently argued for the recognition of the country’s status as a co-belligerent.

Re-established immediately after those events, the daily Viitorul became under his leadership an instrument of struggle for the defense of democratic freedoms. His editorials, vehement and direct, denounced Soviet pressure and the communists’ attempts to seize power. Precisely for this reason, his political opponents mockingly renamed the newspaper “Vitriol.”

Open conflict with the communists

The year 1944 also marked Mihail Fărcășanu’s re-election as president of the National Liberal Youth, at the proposal of the historian Gheorghe Brătianu. At the same time, the attacks against him intensified.

After the liberation of Northern Transylvania, Ana Pauker delivered a speech in Cluj intended to draw the Hungarian population to the side of the communists, claiming that Hungarians were the majority in most Transylvanian cities.

The reply did not come late. On 19 November 1944, Fărcășanu presided over a meeting of the liberal youth and publicly criticized Ana Pauker’s statements. It was the first open challenge directed against her, and it triggered a violent reaction.

The Stalinist press labeled him an “agent of Goebbels,” an “enemy of the people,” and a “saboteur of the national economy.” Even the publication of the translation of Ernest Hemingway’s novel For Whom the Bell Tolls was interpreted as an act of fascism.

The writer Mihail Villara

Alongside his political activity, Mihail Fărcășanu left an important mark on Romanian literature. Under the name Mihail Villara, he published in 1946 the novel The Leaves Are No Longer the Same, awarded by the Cultura Națională Publishing House and praised by modernist critics.

The book, with autobiographical accents and Western influences, portrayed cosmopolitan student milieus in London and Berlin, the inner conflicts of a disillusioned generation, and the erotic tensions of the era.

The novel remains to this day a landmark of late interwar Romanian literature, marking the artistic maturity of an author who was soon to be forced into silence by history.

The pro-royalist demonstration and the beginning of persecution

Another crucial moment was the pro-royalist demonstration organized on King Michael’s name day, on 8 November 1946. Mihail Fărcășanu was among its main organizers. The repression was harsh: over one thousand students were arrested, and the liberal leaders definitively entered the sights of the Stalinist authorities.

That same year, Fărcășanu published the militant volume Letters to Romanian Youth, which was almost immediately banned. The atmosphere was becoming unbreathable, and arrest seemed only a matter of time.

The plan of the aerial escape

In this dramatic context, Mihail Fărcășanu and Vintilă Brătianu devised an unprecedented escape plan. Decisive help was to come from the legendary pilot Matei Ghica-Cantacuzino. The escape was to take place in October 1946, from a small military airfield in Caransebeș.

The strategy was ingenious. An old bomber, recently repaired, was to be returned to its base in Brașov. A governmental commission inspected the aircraft, ensuring that there were no stowaways and that the fuel tank contained only enough gasoline for approximately 300 kilometers. In reality, the mechanic, in complicity with the pilot, had altered the fuel gauge: the aircraft’s tank was full.

Takeoff under the eyes of the authorities

Near the runway, hidden in the bushes, were Mihail Fărcășanu, his wife Pia, and Vintilă Brătianu. The aircraft began taxiing with only the pilot and the flight mechanic on board, under the watchful eyes of the commission from Bucharest.

At the end of the runway, in a spot outside the visual range of the small control tower, the fugitives quickly jumped into the aircraft. The engines were pushed to full power, and the bomber lifted off almost instantly. The communists were left powerless, witnesses to an escape impossible to stop.

Pursuit and the crossing of the Adriatic

In Yugoslav airspace, the aircraft was spotted by fighter planes. Matei Ghica-Cantacuzino maneuvered with exceptional skill, flying among clouds to avoid interception. Nevertheless, the Yugoslav planes opened fire, and the bomber was hit.

With fuel nearly exhausted and with all onboard instruments destroyed except the altimeter, the crossing of the Adriatic Sea became an act of desperation. In the end, the crew managed to land at a military airfield in Bari, Italy, exhausted but alive.

Diplomatic rescue and the birth of a legend

The British officer Ivor Porter, a close friend of the fugitives and an agent of the Special Operations Executive at the British Legation in Bucharest, had sent in advance a telegram to Bari. Thanks to this message, Fărcășanu and his companions were immediately taken under the protection of the British air forces. In its absence, there was a real risk that they might be sent back to Romania.

The episode was described by Ivor Porter in his memoir Operation Autonomous, the book that definitively established this escape as one of the most spectacular in Eastern Europe. The flight was also recalled by Pia Pillat Edwards, under the pseudonym Tina Cosmin, in the autobiographical novel Flight Toward Freedom. Letters from Exile.

Exile and the struggle beyond the borders

From Italy, Mihail Fărcășanu settled in France, where he actively participated in coordinating the Romanian anti-communist exile. In the Paris-based magazine Luceafărul, coordinated by Mircea Eliade, he published the short story The Wind and the Dust, his final literary text, an intense war prose set in Bucharest during the confrontations immediately following 23 August.

He later settled in the United States, becoming an important figure of the Cold War on the Romanian front. He collaborated with Nicolae Rădescu and Grigore Gafencu, co-founded the League of Free Romanians, and served as the first director of the Romanian section of Radio Free Europe between 1951 and 1953. He delivered lectures, founded cultural and journalistic associations, and remained a constant voice of the exile community.

The final years and the silence of history

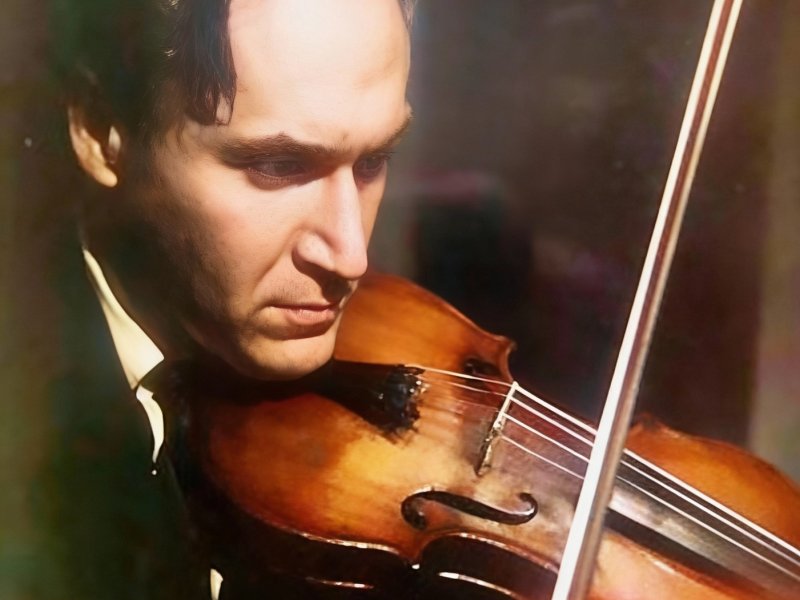

After his divorce from Pia Pillat in 1952, Mihail Fărcășanu remarried three years later to Louise, the widow of American diplomat Franklin Mott Gunther. He spent his final years in his own house in Washington, cared for by his sisters. He lived quietly, played the violin daily, and read, far from public life.

After his death, literary history kept him mostly at the margins, although his destiny remains emblematic. Mihail Fărcășanu’s life illustrates the drama of an intellectual elite forced to choose between compromise and freedom. And “Operation Autonomous” remains the symbol of an escape not only from a country, but from an age of fear.

We also recommend: Who sculpted the Broken Violin Fountain. The history of one of Bucharest’s most spectacular monuments