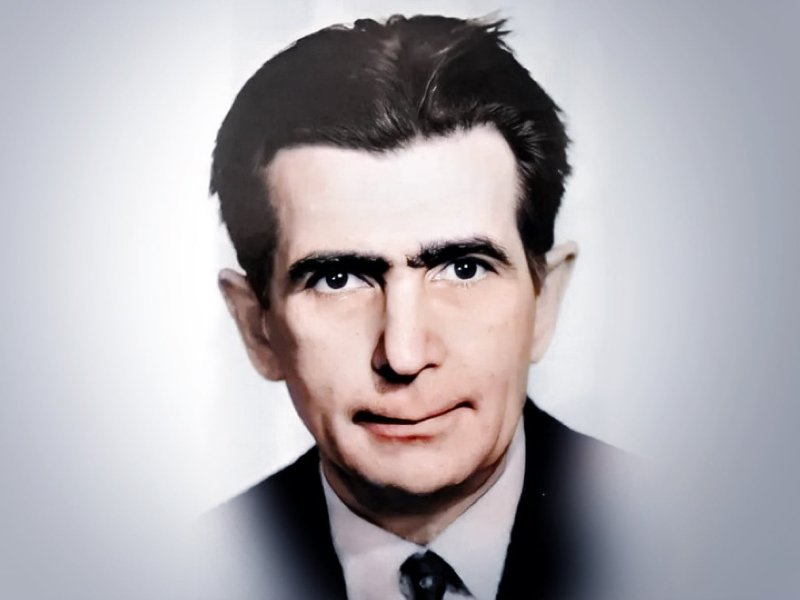

Who was Matei Balș, the blue-blooded doctor after whom Romania’s most famous infectious disease institute was named

By Andreea Bisinicu

- Articles

In Romanian history, there are figures who managed to combine two seemingly incompatible worlds: aristocracy and science, tradition and modernity, a personal destiny marked by hardship and a brilliant career. Among these names is Professor Matei Balș, the doctor who became a symbol of the fight against infectious diseases and of excellence in research, but who also endured the tragedy of being persecuted for his noble origins.

An aristocrat in an age hostile to elites

Born in Bucharest in 1905 into a family with centuries-old boyar roots, Matei Balș seemed destined for a privileged life. His father, George Balș, descended from the Sturdza family branch, while his mother, Marieta Știrbey, was a direct descendant of Constantin Brâncoveanu.

This lineage placed him among the “blue-blooded children” of the early 20th century, but with the advent of communism it also branded him with the stigma of an “unhealthy origin.”

Far from being just an aristocrat, Balș built for himself an exceptional professional reputation. He graduated from the Faculty of Medicine in Bucharest in 1930 and continued his training at the prestigious Pasteur Institute in Paris, where he specialized in bacteriology. The French experience broadened his horizons and transformed him into a doctor of European stature.

Disciple of Cantacuzino and the Eastern Front experience

Returning to Romania after his specialization, Balș had the opportunity to work with Ioan Cantacuzino, his uncle and one of Europe’s greatest microbiologists.

This collaboration was defining for his career. In Cantacuzino’s laboratory, Balș learned not only scientific rigor but also what it meant to lead by example and to inspire entire generations of physicians.

World War II brought another trial. In 1942, he was appointed head of a military hospital on the Eastern Front. Direct contact with the suffering of soldiers, the lack of resources, and the harsh conditions steeled him as a doctor and confirmed his vocation.

Yet this experience would later be used by the communist authorities as a pretext for suspicion and marginalization.

Persecuted for his boyar origins

After the communists came to power, Balș’s career was almost destroyed. For the new regime, aristocracy was a class enemy, and he came from one of the oldest noble families in the country.

In those years, his brother Alexandru Balș paid the ultimate price: arrested on fabricated charges of “high treason,” he died in Pitești prison, deprived of medical care.

Matei Balș was not spared either. He was expelled from medical education, labeled a “landowner’s beast,” and allowed to work only as an associate professor, with limited resources and a small team.

This was the most difficult period of his life: a man trained in Europe’s great universities was silenced and prevented from contributing to medical progress.

Restored as full professor at the Faculty of Medicine in Bucharest

The situation changed partially in 1956, when he was reinstated as a full professor at the Faculty of Medicine in Bucharest. In the 1960s, with a degree of regime relaxation, his career experienced a spectacular revival. In 1962, he was appointed dean of the Faculty of Medicine, a position he held for a decade.

During this time, he modernized the university curriculum, introduced new disciplines such as clinical bacteriology, and supported innovative research. His work was published in hundreds of scientific articles, recognized both in Romania and in international journals.

In difficult medical cases, colleagues instinctively turned to him, and the expression “let Dr. Balș come too” became proverbial in the medical world.

Matei Balș, a researcher of international stature

His activity was not limited to education. Matei Balș was a passionate researcher, always seeking new solutions for infectious diseases threatening public health.

One of his greatest achievements was developing a nitrofuran-based treatment for typhoid fever, a disease that ravaged at the time. For this discovery, he received the First-Class State Prize—an ironic gesture, considering that the same regime that awarded him had persecuted him for years.

Balș was also recognized internationally: he became a member of the Academy of Medicine and of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in the United Kingdom, confirming his scientific authority.

Personal life and the strength to endure

Beyond his career, Balș’s personal life was marked by the contrast between family stability and historical tragedies.

In 1936, he married Lucia Cantacuzino, herself from a traditional family. Together they had two children: Marina, who chose architecture, and Ion, an engineer; both later settled in Switzerland.

Even in difficult years, Balș remained a free spirit. He did not shy away from criticizing bureaucratic absurdities and wrote lucidly about his struggles with an inefficient system:

“I often fought with windmills… with the power of incompetence and the irresponsibility of certain people,” he noted in a text that still circulates today as proof of his integrity.

The fatal aneurysm that ended his life

His destiny ended in 1989, in Geneva, where he died from an aneurysm, shortly before the fall of the communist regime. It was one of history’s ironies: a man marginalized by the authorities passed away without living to see the collapse of the system that had stigmatized him.

Still, his legacy remained. Romania’s most renowned infectious disease institute today bears his name: the National Institute of Infectious Diseases “Prof. Dr. Matei Balș” in Bucharest. This institution, at the forefront of the fight against epidemics—from HIV to the COVID-19 pandemic—continues the spirit and values of one of Romania’s greatest infectious disease specialists.

Matei Balș was more than a doctor. He was a man who proved that professional excellence cannot be silenced by ideology, that medical vocation knows no political barriers, and that true specialists leave their mark on future generations, regardless of the times.

Although he came from a noble family, Balș earned his reputation through hard work, passion, and his ability to reinvent himself even when history was against him. His life remains an example of how the aristocracy of blood can be doubled by the aristocracy of spirit and knowledge.

Today, when his name is spoken daily by thousands of patients and doctors who enter the institute that bears it, the memory of Matei Balș takes on a living, current dimension. He is a model of courage, professionalism, and humanism—an aristocrat of Romanian medicine in the deepest sense of the word.